SUSTAINABLE SEA PORT CLUSTERS WITHIN GREEN TRANSPORT CORRIDORS

Gunnar Prause, Professor

Tallinn University of Technology

School of Economics and Business Administration

Akadeemia tee 3, 12618 Tallinn, Estonia

Tel: +372 53059488 E-Mail : ********** ********** ttu.ee

1. Abstract

Sea ports play an important role in global trade and for economic growth even when taking into account that global maritime traffic undergoes a high level of concentration into a limited number of large ports. An important characteristic of the majority of sea ports is their contribution to economic growth and regional development based on their surrounding logistics intensive clusters usually comprising enterprises from service and industrial sector.

In Europe a large number of seaports play an important role as logistics hub in the concept of green transport corridors so that their development has to be oriented towards the needs of logistics service node as a part of the hub network of a green transport corridor as well as towards their own targets as a sea port cluster. Both concepts the green transport corridor as well as the sea port cluster embrace common aims like sustainability and inter-organizational cooperation but there are also conflicting objectives.

Since the author took part in some important green transport corridor initiatives around the Baltic Sea, the paper presents results about sustainable development of seaport clusters which are at the same time transshipment hubs in green transport corridors. The discussions will be enriched by empiric data and case studies from several EU projects.

Keywords: sustainability, port and hub development, sea port clusters, green transport corridors

2. Introduction

Besides its role in international trade, sea ports appear as part of the supply chains of companies involved, through upstream and downstream linkages, where the competition is not between individual ports but between logistic chains (Meersman and Van de Voorde, 1996). But even when taking into account that global maritime traffic undergoes a high level of concentration in a limited number of large ports the contribution of seaports goes far beyond their cluster borders and impacts significantly the economic growth of the near hinterland due to cheap maritime transportation (Hausmann, 2001). These facts have been studied intensively for the larger ports, acting as gateways of continental distribution and transhipment hubs, which are provided with an access to powerful hinterland links and high capacity inland freight distribution corridors, where notably rail is compulsory to face acute congestion problems to safeguard quick forwarding of cargo. These gateways have seen the development of port-centric logistics activities that support export and import-based activities (Rodrigue et al., 2013).

In recent years, on European level an increasing number of initiatives have been started and realised to speed up the shift towards greener and more efficient freight logistic solutions in Europe. Important steps on EU level in this development process have been the Freight Transport Action Plan from 2007, the Green Paper on TEN-T from 2009, as well as the TEN-T Policy Review 2011 and the EC White Paper on "A Sustainable Future of Transport" (FTAP, 2007; COM, 2009; 2011).

In the context of these European initiatives the logistics hub functions of seaports appear to go beyond the traditional role as gateways towards the concept of green transport corridors, i.e. as transhipment routes with concentration of freight traffic between major hubs and by relatively long distances of transport marked by reduced environmental and climate impact while increasing safety and efficiency with application of sustainable logistics solutions (COM, 2011). The transport within these green transport corridors is based on inter-modality, powerful logistics hubs, specific organisational frame conditions and advanced ICT-systems improving traffic management, increasing efficiency and better integrating the logistics components of such a corridor (Prause and Hunke, 2014b).

The role of seaports in the context of green transport corridors is manifold since it stresses the ecological dimension in seaport development as well as the development of logistics service node as part of the hub network of a green transport corridor (Peris-Mora, 2005; Braathen, 2011). So the green dimension for seaports will become more important due to new ecological developments in transportation, especially maritime transportation, like the implementation of SECA and NECA areas from 2015 in some parts of Europe which are assumed to impact existing port services.

The development of a seaport alone represents already a big challenge since seaports differ in their portfolio of products and services depending on the geographical location and on their connection to different transport modes and, in an extended form, on the provision of services in the field of warehousing, distribution, and (logistics related) services (van der Lugt and DeLangen, 2005; Grundey and Rimi, 2007; Jaržemskis, 2007). Yossi Sheffi (2013) coined the term of a logistics intensive cluster and in his perception a seaport can be considered as a logistics intensive cluster to which also possible non–logistical businesses can be connected or linked like production companies or maritime industry. But the complexity of developing a seaport cluster increases heavily in the situation where a seaport fulfils beside its traditional role simultaneously the function of a transhipment hub within a green transport corridors because in this case the focus on sustainable cluster development has to be additionally laid on inter-modality, compliance with specific organisational and ICT frame conditions and hub development needs to be related to the green transport corridor (Prause, 2014b).

Thus sustainable seaport development along transhipment routes of green corridors requires specific monitoring, management and governance structures, safeguarding good performance of the seaport cluster which is in line with the requirements of the green corridors and which will meet the current and future transport and service demand as seaport. But until now, only little research has been carried out on the development of seaports within green transport corridors (Prause, 2014a). Peter DeLangen (2004) proposed a framework for the assessment of the performance of seaport clusters and Chui et al. (2014) discussed a five dimensional measurement of green port operation. But until now, only a little research has been carried out on a holistic approach for sustainable development of seaport clusters and a literature review indicates a research gap in the field of sustainable development of seaport clusters within green transport corridors recognizing the multiple aspects of roles of seaports including their functions as main corridor transhipment hubs, as logistics clusters as well as green node in green supply chains.

The aim of the paper is to propose an integrated assessment system for green seaport cluster clusters and discusses the compatibility of frame conditions for sustainable development of seaport clusters acting as transhipment hubs in green transport corridors. The discussions will be based on empiric data and case studies from several important European green transport corridor initiatives around the Baltic Sea. A special focus will be laid on the Green Transport Corridor “EWTC2: East-West Transport Corridor” representing the first European project which delivered a green corridor manual formulating a KPI system for management and monitoring for green corridors together with recommendations and requirements of green transport corridors at European level.

3. Theoretic frameAccording to Simchi-Levy et al. (2003) supply chain management consists of a set of approaches utilized to efficiently integrate suppliers, manufacturers, warehouses, and stores, so that merchandise is produced and distributed at the right quantities, to the right locations, and at the right time, in order to minimize system wide costs while satisfying service level requirement. By following this view, supply chain management deals with the whole cross-company value chain including suppliers, manufactures, customers and disposal companies which are involved in the supply chain activities.

This approach also paves the way for a discussion about the role of sea ports as parts of supply chains. Paixão and Marlow (2003) considered the potential application of agile supply chain strategy to ports and they identified the role of ports in supply chains with the contribution of large terminal operators in the process of integration with the other actors of the supply chains. Bichou and Gray (2004) conceptualised the port system from a logistics and supply chain management perspective by aiming to define a new framework to measure port performance. Tongzon et al. (2009) analysed port’s supply chain orientation from the perspectives of port’s services providers, i.e. the terminal operators, and the shipping companies and they measured the extent to which the shipping companies perceive terminals to be supply chain oriented and investigate whether there is a convergence of perceptions between terminals and shipping companies. De Martino et al. (2010) considered the port as a network of actors, resources and activities, which co-produce value by promoting a number of interdependencies among the supply chains passing through the port.

As already Robinson (2002) pointed out, a port can be considered as a Third Party Logistics (TPL) provider that intervenes in a series of different companies’ supply chains and he stressed in his paper the integrative practices undertaken by shipping companies for the supply of complex logistical services, from intermodal transport to distribution of goods. In this understanding a port is a destination for a specific “logistics intensive cluster” in the sense of Sheffi (2012, 2013), i.e. an agglomeration of several types of firms and operations providing logistics services and logistics operations of industrial firms and operations of companies for whom logistics is a large part of their business. Such logistics clusters also include firms that provide services to logistics companies like maintenance operations, software providers, specialized law firms or international financial services providers. Reality shows that existing seaport clusters may even include non–logistics stakeholders like production companies or maritime industry.

Recent approaches extended supply chain management towards green supply chain management by adding sustainability, i.e. integrating environmental thinking, including product design, material sourcing and selection, manufacturing processes, delivery of the final product to the consumers, and end-of-life management of the product after its useful life (Shrivastava, 2007). As Adams (2006) stressed the core of mainstream sustainability thinking has become the idea of three dimensions, environmental, social and economic sustainability.

There exists interdependency between conventional supply chain management and eco-programs (Sarkis 2001). This includes the approach on how ecological aspects can be considered in the whole business processes in the most effectively way. Hervani et al. (2005) proposed that green supply chain management practices include green purchasing, green manufacturing, materials management, green distribution/marketing and reverse logistics. Therefore, it can be assumed that the involvement of green aspects in the supply chain of a company also involves changes in the supply chain itself. Of course, this will have an impact on the cooperative alliances with suppliers, manufactures and the customer at the end of the logistics chain but green supply chain management can lead to better performance in terms of indicators such as environmental protection, efficient usage of resources and even to additional turnover due to a green company image and reputation (Hunke and Prause, 2014).

Green supply chain issues have been also studied by several scholars in the context of ports and their port operations but it seems that the discussions are rather diverse. Recent approaches are focussing on the minimization of environmental effects trying to improve the environmental footprint of a port by introducing new technologies and renewing their infrastructure while avoiding unnecessary energy use (Chui et al., 2014). Further literature review leads to a categorisation into five dimensions of measurement of green port operation (Darbra et al., 2005; Peris-Mora et al., 2005; Bailey and Solomon, 2004; Klopott, 2013; Chiu and Lai, 2011). Chui et al. (2014) pointed out how these five dimensions can provide more detailed information to enhance the greenness of a port and its operations.

The concept of Green Transport Corridors (GTC), introduced by European Commission (EC) in their Freight Transport Logistics Action Plan (FTLAP, 2007) and has been further specified in the EU White Paper on Transport in 2011 (COM, 2011). The GTC concept goes beyond the consideration of single logistics and transhipment hubs, by targeting the implementation of European transhipment routes with concentration of freight traffic between major hubs and relatively long distances of transport marked by reduced environmental and climate impact, while increasing safety and efficiency with application of sustainable logistics solutions, inter-modality, ICT infrastructure, common and open legal regulations and strategically placed transhipment nodes.

Green transport corridors are related to green or sustainable supply chain issues, multimodality and network concepts as Hunke and Prause (2013) pointed out, so that green supply chain management belongs to the theoretical foundations of GTC as well as cluster theory since green transport corridor itself can be considered as a “tubular logistics service cluster”. Thus important logistics hubs within the network of nodes of a GTC fulfil the properties of a logistic intensive clusters in the sense of Yossi Sheffi (2012, 2013) differing in their portfolio of products and services depending on the geographical location and on their connection to different transport modes providing specific services in the field of warehousing, distribution, and (logistics related) services (Porter, 2000; van der Lugt and DeLangen, 2005; Grundey and Rimi, 2007; Jaržemskis, 2007; Daduna et al., 2012; Prause and Hunke, 2014b).

But the complexity of sustainable development of a seaport cluster increases dramatically when the seaport adopts simultaneously the function of a transhipment hub within a green transport corridor due to additional tasks related to inter-modality, organisational frame conditions and GTC–specific hub development needs (Prause and Hunke, 2014b; Prause, 2014b).

4. Sustainable Development of Seaport ClustersLogistics clusters, also logistics intensive clusters, enjoy the same advantages that general industrial clusters, i.e. the increase of productivity due to shared resources and availability of suppliers, improved human networks, including knowledge sharing, tacit communications and understanding, high trust level among companies in the cluster, availability of specialized labour pool as well as educational and training facilities, and knowledge creation centres, such as universities, consulting firms, and think tanks (Sheffi, 2013). Seaport clusters represent a special form logistics clusters which are often linked also to non–logistics cluster members like production companies or maritime industry. Seaport clusters and their sustainable development have been studied by several scholars (DeLangen, 2004).

In the special case of seaports acting as container–based transhipment hubs their hub function is known as Seaport Container Terminals (SCT) usually equipped with multimodal linkages realising port-hinterland container logistics featuring physical and information flows among actors and nodes which are operating in port-hinterland networks in order to organise powerful and efficient container distribution systems (Notteboom, 2008; Roso et al., 2009; Rodrigue and Nottebaum, 2009; Rodrigue and Notteboom, 2010; Daduna, 2011). But it also has to be mentioned that seaport container terminals have their own specific problems and challenges so that the related research follows their specific frame conditions which are too narrow in order to describe the situation of general seaport clusters.

An important framework for the assessment of general seaport clusters was developed and proposed by Peter de Langen (2004) in his PhD thesis and he was able to point out that the performance of seaport clusters can be described by a set of eight variables where four variables are expressing the cluster structure and the other four variable are describing the cluster governance (table 1).

Table 1: Assessment of sea port clusters (DeLangen, 2004)

| Cluster Structure | Cluster Governance |

| Agglomeration economies • A shared labour pool attracts firms • The presence of customers and suppliers attracts firms to the cluster. • The presence of knowledge (spill-over) attracts firms to the cluster. • Land scarcity and high land prices ‘disperse’ firms from the cluster. • Congestion disperses firms | The presence of trust • Trust lowers coordination costs because costs to specify contracts decrease. • Trust increases the scope of coordination beyond price, because the risk of free riding decreases. |

| Internal competition • Internal competition prevents monopoly pricing • Internal competition leads to specialization. • Internal competition promotes innovation | The presence of intermediaries • Intermediaries lower coordination costs and increase the scope of coordination beyond price because they specialize in managing coordination. |

| Cluster barriers • Entry barriers and start-up barriers reduce competitive pressure and prevent the inflow of (human) capital. • Exit barriers reduce uncertainty for firms in the cluster. | The presence of leader firms • Leader firms generate positive external effects in their network encouraging innovation and promoting internationalization. • Leader firms generate positive external effects by organizing investments in training and education, innovation and infrastructure |

| Cluster heterogeneity • Cluster heterogeneity enhances opportunities for innovation. • Cluster heterogeneity enhances opportunities for cooperation. • Cluster heterogeneity reduces vulnerability for external shocks. | Quality of collective action regimes • The more resources are invested in collective action regimes influence the amount of invested resources: O role of leader firms, O role of public organizations, O presence of an infrastructure for collective action, the presence of a community argument O use of voice. |

The verification of his approach was done by testing his analytical framework in empirical assessments of the three seaport clusters of Rotterdam, Durban and the Lower Mississippi Port Cluster. The results of his approach allowed Peter de Langen to reveal strengths and weaknesses in the current status of the investigated seaport clusters so that he was able to provide recommendations for improving the performance and to outline directions for a sustainable development of these clusters. In the sequel other seaport clusters were analysed in accordance with de Langen’s approach, i.e. the Easter German Seaport Cluster of Rostock (Prause and Hunke, 2014a).

De Langen published his framework before green supply chain management issues climbed to the top of the logistics agenda, so his approach neglected green aspects of seaports. This research gap has been filled by other scholars and a synthesis of the academic discussion can be found in the concept of Chiu et al. (2014) who were able to identify, based on literature review and empiric activities, and by using Fuzzy Analytical Hierarchy Process (FAHP) methodology, five dimensions of green port operations together with 13 highly relevant factors providing detailed information about suitable actions to enhance the greenness of port operations (table 2).

Table 2: Dimensions of green port operations (Chiu et al., 2014)

| Dimensions | Relevant Factors |

| Environmental quality | · Pollution of water, air, noise, land and sediment |

| Use of energy and resource | · Usage of energy, water and materials |

| Habitat quality and greenery | · Port greenery and habitat quality maintenance |

| Waste handling | · Handling of general and hazardous waste |

| Social participation | · Port staff training, community promotion and education |

Until now a holistic approach for an integrated assessment system for green or sustainable seaport cluster development is missing. In the ideal case such a holistic approach should satisfy all dimensions of seaport cluster assessment, i.e. the cluster structure and cluster governance dimensions from de Langen (2004) as well as the dimensions of green port operations of Chiu et al. (2014). By following Sarkis (2001) interpretation of green supply chains as an interdependency between conventional supply chain management and eco-programs, and transferring his approach analogously to green seaports a suitable concept for assessing the performance of green seaport clusters can be achieved by integrating both concept of de Langen and Chiu, Lin and Ting, so that an integrated assessment system for green, respectively sustainable, seaport cluster development can be achieved by the following construction, based on 13 variables (table 3).

Table 3: Integrated assessment system for green seaport clusters

| Cluster Structure | Cluster Governance | Cluster Sustainability |

| Agglomeration economies | The presence of trust | Environmental quality |

| Internal competition | The presence of intermediaries | Use of energy and resource |

| Cluster barriers | The presence of leader firms | Habitat quality and greenery |

| Cluster heterogeneity | Quality of collective action regimes | Waste handling |

|

| Social participation | |

After joining the two seaport cluster approaches the new assessment concept has to be checked for logical coherence, i.e. it must be verified that the new concept is not causing logical contradictions and that the underlying variables are mutually independent. The coherence check has been done by the author by allying the new assessment concept to two cases, the seaport clusters of Hamburg and Rostock in Northern Europe, since the author has been involved in research activities in both seaport clusters (Biebig and Prause, 2007; Prause and Hunke, 2014a; Prause, 2014). Neiter of the case studies did not lead to logical contradictions and there was also no indication of depending variables of the integrated assessment system for green seaport clusters.

5. Sustainable Development of Green Transport CorridorsGreen transport corridors represent transhipment routes with a concentration of freight traffic between major hubs and long distances of transport marked by reduced environmental and climate impact. Their underlying network and supply chain structures requires powerful management control systems concentrating on multi-dimensional evaluation of collective strategies and processes in an international environment with a focus on cross-company aspects. The current scientific discussion stresses operational aspects of the corridor performance mainly based on Key Performance Indicators (KPI) so that strategic components are needed to safeguard an efficient, innovative, safe and environmentally friendly long-term development (Prause, 2014b).

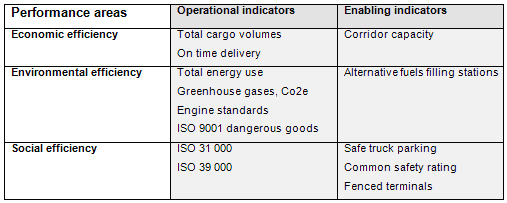

The KPI system which has been developed and empirically verified in the frame of the green corridor project “East-West Transport Corridor (EWTC)” and which has been published in the “EWTC Green Corridor Manual” represents an important step ahead (EWTC, 2012). An important feature of the EWTC – KPI system is its distinction between enabling criteria, describing the capacities and settings of the transport chain in regard to the hard infrastructure, and operational criteria which are highlighting the organisational and soft infrastructure of the corridor. The performance areas of the EWTC – KPI system are oriented on the three classical dimensions of sustainability by considering the economic, environmental and social aspects of efficiency (Table 4).

Table 4: EWTC KPI system (EWTC 2012)

Besides the fact that the EWTC – KPI system is very general and oriented more on land transportation, another important issue is its focus on operational aspects. All currently discussed sets of Key Performance Indicators (KPI) for green transport corridors have in common that they neglect network-oriented aspects, so that a general concept for a green corridor management control system is still missing (Sydow and Möllering, 2009; Hunke and Prause, 2013; Prause, 2014a). A possible solution is to apply the balanced scorecard concept of Kaplan and Norton (1996) in combination with a green supply chain approach to green transport corridors in order to solve the strategic weakness of the existing concepts.

Weber (2002) discussed a cross-company balanced scorecard for supply chains integrating two perspectives of network–oriented aspects which he called cooperation intensity and cooperation quality. Prause and Hunke (2014b) exhibited that besides the criteria covered by the EWTC – KPIs other aspects like openness, transparency, fair and harmonised access regulations as well as cooperation aspects are common and characteristic frame conditions for green transport corridors. Based on these results Prause (2014b) proposed a strategic management control system for green transport corridors in shape of a green corridor balanced scorecard which includes the KPI system of the EWTC “Green Corridor Manual” and which respects also the frame conditions of a GTC (table 5).

Table 5: A balanced Scorecard for Green Transport Corridors (Prause, 2014b)

· Sustainability perspective

o Economic efficiency

o Environmental efficiency

o Social efficiency

· Growth perspective

o Innovation activities

o New services

o Green corridor stakeholder fluctuation

o TO of new services

· Cooperation intensity

o Data exchange

o Coordination needs

· Cooperation quality

o Openness

o Trust level

o Transparency level

o Conflict level

This balanced scorecard approach is in line with supply chain management control system and includes all important perspectives for green transport corridors by taking into account the underlying network properties of a corridor. Furthermore, it constitutes the KPI system of the EWTC2 project but nevertheless it has to be pointed out that the set of indicators is not complete and also the type of measurement and evaluation of the indicators is still open so that further research has to be done to mature and complete the concept (Schröder and Prause, 2015).

6. Sustainable Development: Seaport Clusters vs. Green Transport CorridorsLogistics clusters, acting as hubs within green transport corridors, play a crucial role for multimodal transportation since one important goal is to facilitate modal shifts in order to consolidate the fright flows managed by the transport and logistics operators and to offer convenient transport and synergic solutions based on rail, road, inland waterways or short-sea-shipping by using instance block shuttle trains on long-range journeys (Europlatforms EEIG, 2004; COM, 2011). In this sense seaport clusters are already integrated with their multi-modal hinterland links in transport corridors as nodes or transhipment hubs. Successful cases of such seaport clusters are the European North Range ports which all found their individual hinterland transportation mode mixes.

But the implementation of green transport corridor concepts goes one step further due to the stronger organisational frame conditions comprising openness, fair and balanced access as well as the cooperative interaction of large firms and SMEs setting high requirements for seaport clusters within such corridors (Prause, 2014a, 2014b). Consequently, a coherent and sustainable cluster development of seaport clusters within green transport corridors requires compatible objectives respecting the needs of sustainable seaport clusters as well as green transport corridors. A necessary compatibility check of the objectives of both sustainable development concepts can be started by comparing the aims of the integrated assessment system for green seaport clusters from table 3 and the balanced scorecard approach for green corridors from table 5.

Firstly, is can be observed that a cooperation dimension exists in both approaches. The cooperation dimension in the green corridor balanced scorecard (table 5) comprises the cooperation intensity and the cooperation quality including the levels of trust and transparency as well as the degree of openness whereas the integrated assessment system for green seaport clusters (table 3) disposes of the cluster governance dimension which covers comparable objectives as the green corridor balanced scorecard. Secondly, the comparison of both approaches reveals that the sustainability objectives of green transport corridors as well of green seaport clusters are following similar aims even if the objectives of seaports are more specific pertaining to the needs of harbours compared to those of green transport corridors which targets are more general and more land transportation oriented.

The growth perspective of green transport corridors requires a special consideration since there exists no explicit dimension of growth in the seaport cluster concept of Peter de Langen (2004). But a closer view at the cluster structure and governance dimensions “The presence of leader firms” and “Quality of collective action regimes” reveals growth related issues comprising of the attraction of firms for the cluster and innovation aspects as well as the topics of investments, internationalisation, training and qualification. Since these issues are growth related, it can be asserted that growth elements are part of both concepts, i.e. the growth dimension appears in the green transport corridor approach as well as in the sustainable seaport cluster concept.

But the comparison also reveals controversial topics in both concepts as the green transport corridor concept requires frame conditions comprising of openness, fair and balanced access to the corridor and its resources as well as the cooperative interaction of leader firms and SMEs which partly found its way into the green corridor balanced scorecard. Otherwise de Langen (2004) stresses in the same context the role of leader firms in cluster governance by referring to the results of Michael Porter’s (1998, 2000) classical cluster theory. In order to evaluate the level of conflict between both concepts a case study from the EWTC project will be considered.

The EWTC project rests upon the two Baltic seaports Karlshamn and Klaipeda which are acting as cornerstones within the corridor and which are linked by short sea shipping lines between both ports; beyond that the port of Klaipeda belongs to the most important ports within the Eastern Baltic Sea region (KPMG, 2013). Both seaports form together with their surroundings a seaport cluster in the sense of de Langen acting as transhipment and logistics hub within the green corridor. Since the concept of the green corridor balanced scorecard is directly based on the outcomes of EWTC project, both seaports can be assessed and further developed in line with the green corridor balanced scorecard approach. A deeper insight into both seaports based on the empiric results of EWTC (2012) confirms that the level of potential conflicts between the integral assessment system for green seaport clusters and the green transport balanced scorecard approach is negligible.

Of special interest is a compatibility check of the role of leading firm like stated in the seaport cluster approach compared to the green corridor frame conditions for openness, fair access and interaction between large companies and the SME sector. In the case of both EWTC ports Karlshamn and Klaipeda there exist leading firms in the sense of de Langen so that the green corridor frame conditions are not yet fulfilled, but the quality of cooperation with other companies in the cluster, especially the interaction with SME’s, can be further evolved in both ports towards a situation so that the objectives of both assessment systems for green transport corridors as well as for the integrated systems for green seaport clusters of de Langen (2004) and Chiu et al. (2014) can be achieved. This objective will be one of the main outputs of an upcoming EU initiative representing a follow-up of the EWTC project.

7. ConclusionThe concept of Green Transport Corridor plays an important role on the European transport agenda and the sustainable development of green corridors depends strongly on the underlying transport network and their related nodes and transshipment hubs. Seaports often represent important hubs in green transport corridors and their sustainable development together with their surrounding seaport clusters follows their own pathways which are managed and controlled according to specific performance evaluation concepts. The research presented an integrated assessment system for green seaport clusters based on literature research and case studies and compared it to a balanced scorecard approach for green transport corridors which is based on empiric evidences and literature review.

The main results of the research reveal that the assessment systems for green seaport clusters can be combined in a coherent way with the objectives of a green corridor balanced scorecard so that a sustainable development of a seaport cluster acting simultaneously as hubs within a green transport corridors is possible and can be controlled by coherent assessment systems. The empirical verification of this result has been carried out based on the case studies of two seaport clusters Karlshamn and Klaipeda which have been part of the EWTC project. Of course more research has to be done in order to develop a holistic management control system for sustainable development of seaport clusters which is in compliance with both concepts and related frame conditions.

References

Adams, W.M. (2006). "The Future of Sustainability: Re-thinking Environment and Development in the Twenty-first Century." Report of the IUCN Renowned Thinkers Meeting, 29–31 January 2006

Alicke, K. (2002). Modelling and optimization of the intermodal terminal Mega Hub. In: OR Spectrum 24, 1–17

Bailey, D.; Solomon, G. (2004). “Pollution prevention at ports: clearing the air,” Environmental Impact Assessment Review, vol. 24, no. 7-8, pp. 749–774

Bichou, K., & Gray, R., (2004), A logistics and supply chain management approach to port performance measurement, Maritime Policy & Management, 31(1), 47 – 67

Biebig, P.; Prause, G. (2007). Logistik in Mecklenburg-Entwicklungen und Trends, WDP 7/2007, Wismar University

Chiu, R. H.; Lai, I. C. (2011). “Green port measures: empirical case in Taiwan,” in Proceedings of the Eastern Asia Society for

Transportation Studies, vol. 8, pp. 1–15, The Eastern Asia Society for Transportation Studies, Jeju, Republic of Korea.

Chiu, R. H.; Lin, L. H.; Ting, S. C. (2014). Evaluation of Green Port Factors and Performance: A Fuzzy AHP Analysis, Mathematical Problems in Engineering, Volume 2014, Article ID 802976, http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2014/802976

COM (2009). Green Paper "TEN-T : A policy review – Towards a better integrated trans-European transport network at the service of the common transport policy", Brussels

COM (2011). Roadmap to a Single European Transport Area – Towards a competitive and resource efficient transport system. Commission of European Communities. Brussels, 28.03.2011

Daduna, J. R. (2011). Importance of hinterland transport networks for operational efficiency in seaport container terminals. In: Böse, J.W. (ed.): Handbook of Terminal Planning. (Springer) New York et al., 381–397

Daduna, J.; Hunke, K.; Prause, G. (2012). Analysis of Short Sea Shipping-Based Logistics Corridors in the Baltic Sea Region. Journal of Shipping and Ocean Engineering, 2(5, Serial Number 8), 304 - 319

Darbra, R. M.; Ronza, A.; Stojanovic, T. A.; Wooldridge, C.; Casal,J. (2005). “A procedure for identifying significant environmental aspects in sea ports,” Marine Pollution Bulletin, vol. 50, no. 8, pp. 866–874

De Langen, P. W. (2004). The Performance of Seaport Clusters. TRAIL Thesis Series, No. T2004/1. ISBN 90-5892-056-9

De Martino, M.; Marasco, A.; Morvillo, A. (2010). "Value Creation within Port Supply Network: Methodological Issues"., 26th Industrial Marketing and Purchasing Group Conference, 2-4 September 2010, Budapest, Hungary.

EUROPLATFORMS EEIG (2004). Logistics Centres – Directions for Use, Brussels

EWTC (2012). EWTC II Green Corridor Manual. Green Corridor Manual – Task 3B of the EWTC II project. NetPort.Karlshamn

FTLAP (2007). Communication from the Commission: Freight Transport Logistics Action Plan. Commission of European Communities. Brussels, 18.10.2007

Green Corridor (2010). Regeringskansliet – Government Offices of Sweden, Green Corridors

Grundey, D.; Rimiené, K. (2007). Logistic centre concept through evolution and definition. In: Engineering Economics 54 (4), 87–95

Hausmann, R. (2001). Prisoners of Geography, Foreign Policy, 1/2001

Hervani A.A., M.M. Helms, J. Sarkis (2005). Performance measurement for green supply chain management. Benchmarking: An International Journal, 12 (4) (2005), pp. 330–353

Hess, T. (2002). Netzwerkcontrolling: Instrumente und ihre Werkzeugunterstützung. Wiesbaden

Hippe, A. (1997). Interdependenzen von Strategie und Controlling in Unternehmensnetzwerken, Wiesbaden

Hunke, K.; Prause, G. (2012). Hub Development along Green Transport Corridors in Baltic Sea Region . Blecker, T.; Kersten, W.; Ringle, C. (Toim.). Pioneering Supply Chain Design (265 - 282). Hamburg University of Technology

Hunke, K.; Prause, G. (2013). Management of Green Corridor Performance. Transport and Telecommunication, 14(4), 292 - 299

Hunke, K.; Prause, G. (2014). Sustainable supply chain management in German automotive industry: experiences and success factors. Journal of Security and Sustainability Issues, 3(3), 15 - 22.

Jaržemskis, A. (2007). Research on public logistics centre as a tool for cooperation. In: Transport 23(3), 202–207

Kaplan, R. ; Norton, D. (1996). The Balanced Scorecard. Translating Strategy into Action, Boston

Klopott, M. (2013). “Restructuring of environmental management in Baltic ports: case of Poland,” Maritime Policy and Management, vol. 40, no. 5, pp. 439–450

KPMG (2013). Competitive Positions of the Baltic States Ports, KPMG Baltics, Riga

Notteboom, T. (2008). Bundling of freight flows and hinterland network developments. In: Konings, R. / Priemus, H. / Nijkamp, P. (eds.): The future of intermodal freight transport - Operations, design and policy. (Elgar) Chelten-ham / Northhampton, MA, 66–88

Paixão, A. C.; Marlow P. B. (2003). Fourth generation ports-a question of agility?, International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management, Volume 33, Issue 4, 355-376

Peris-Mora, E.; Orejas, J.; Subirats, A.; Ibanez, S.; Alvarez, P. (2005). “Development of a system of indicators for sustainable

port management,” Marine Pollution Bulletin, vol. 50, no. 12, pp. 1649–1660

Porter, M. (2000). Location, Competition, and Economic Development: Local Clusters in a Global Economy. Economic Development Quarterly, Vol. 14 (1), 15 – 34

Prause, G. (2010a). SME in Service Cluster - A regional Study. In: Kramer, J.; Prause, G.; Sepp, J. (Eds.) Baltic Business and Socio-Economic Development 2007 : 3rd International Conference Tallinn, Estonia, June 17-19, 2007 (349 - 360). Berlin: Berliner Wissenschafts-Verlag

Prause, G. (2010b). Logistics-related Entrepreneurship and Regional Development - An empiric Study. Kramer, J..; Prause, G.; Sepp, J. (Eds.). Baltic Business and Socio-Economic Development 2007 : 3rd International Conference Tallinn, Estonia, June 17-19, 2007 (329 - 348). Berlin: Berliner Wissenschafts-Verlag

Prause, G.; Hunke, K. (2014a). Sustainable Entrepreneurship along Green Corridors, Journal of Entrepreneurship and Sustainability Issues, 1(3), 124 - 133.

Prause, G.; Hunke, K. (2014b). Secure and Sustainable Supply Chain Management: Integrated ICT-Systems for Green Transport Corridors . Journal of Security and Sustainability Issues, 3(4), 5 - 16.

Prause, G. (2014a). A Green Corridor Balanced Scorecard. Transport and Telecommunication, 15(4), 299 - 307.

Prause, G. (2014b). Sustainable development of logistics clusters in Green transport corridors, Journal of Security and Sustainability Issues 4(1): 59–68.

Robinson, R. (2002). Ports as elements in value-driven chain systems: the new paradigm. Maritime Policy and Management, (29), 241-255

Rodrigue, J.-P. (2008). The Thruport concept and transmodal rail freight distribution in North America. In: Journal of Transport Geography 16, 233–246

Rodrigue, J.-P.; Notteboom, T. (2009) The terminalization of supply chains: reassessing the role of terminals in port / hinterland logistical relationships, Maritime Policy & Management, 36(2), pp. 165-183

Rodrigue, J.-P.; Notteboom, T. (2010). Comparative North American and European gateway logistics - The region-alism of freight distribution. In: Journal of Transport Geography 18, 497–507

Rodrigue, J.-P.; Slack, B.; Notteboom, T. (2013). The Geography of Transport Systems, 3[rd] edition, Routledge, New York

Roso, V.; Woxenius, J.; Lumsden, K. (2009): The dry port concept - Connecting container seaports with the hinterland. in: Journal of Transport Geography 17, 338–345

Schröder, M.; Prause, G. (2015). Risk Management for Green Transport Corridors, Journal of Entrepreneurship and Sustainability Issues , to appear

Simchi-Levy, D.; Kaminsky, P.; Simchi-Levy, E. (2003). Designing and managing the supply chain, 2[nd] edition, New York

Sarkis, J. 2001: Introduction. Greener Management International 35(3):21-25

Sheffi, Y. (2012). Logistics Clusters, MIT Press

Sheffi, Y. (2013). Logistics Intensive Clusters: Global Competitiveness and Regional Growth, in James Bookbinder (Ed.), Handbook of Global Logistics, (Springer Science+Business Media, NY 2013), Chapter 19, pp. 463-500

Srivastava, S.K., (2007). Green supply-chain management: a state- of- the- art literature review. International Journal of Management Review, 9 (1) (2007), pp. 53–80

Sydow, J.; Möllering, G. (2013). Produktion in Netzwerken, Verlag Franz Vahlen, 2nd edition, München

Tongzon J., Chang Y-T, Lee S-Y (2009), “How supply chain oriented is the port sector?”, International Journal of Production Economics, 122, pp 21-34

Van der Lugt, L. M.; DeLangen, P. W. (2005). The changing role of ports as locations for logistics activities. In: Journal of International Logistics and Trade 3, 59–72

Weber J. (2002). Logistik- und Supply Chain Controlling, 5th edition, Stuttgart