Brand storytelling

Boryana Gigova, New Bulgarian University

“The best brands are built on great stories.” - Ian Rowden Chief Marketing Officer, Virgin Group

Stories are memorable. Stories travel farther. Stories inspire action. A brand story is more than content and a narrative. Stories help consumers to understand the benefits of a brand, and add favorable and unique associations to a brand. Such associations can lead to an understanding of points-of difference and increase customer-based brand equity. A good story needs to be shared, so that people can be engaged by the story and in doing so, compelled to make it their own. Storytelling is a shared experience among equals in which the audience is just as active participant as the storyteller.Today’s brands are open books where there is no single author of the brand story. Digital technologies have greatly enhanced the consumers’ control in brand building. A brand story should be written collaboratively between the brand and the consumer in an on-going process. Brands need to listen and encourage active participation in order to gain the consumers’ trust and create brand resonance.

Историите се помнят. Историите стигат далеч. Историите подтикват към действие. Историята на бранда е повече от съдържание и разказ. Историите помогнат на потребителите да разберат позитивите на бранда, създават благоприятни и уникални асоциации към него. Такива асоциации могат да доведат до разбиране на точките на различие на бранда и да увеличат клиентски-ориентираната стойност на бранда. Една добра история трябва да бъде споделена, така че хората да могат да я пречупят през собствената си призма и да я направят своя. Сторителингът (Storytelling), или т.н. маркетинг „Нека ти разкажа“, е споделен опит сред равни, в които публиката е също толкова активен участник както и разказвач. Днешните брандове са отворени книги, в които няма само един автор на историята на бранда. Дигиталните технологии значително увеличават контрола на потребителите върхуизгаждането на бранда. Съдържанието като разказ на бранда, трябва да се пише продължително и съвместно между бранда и неговите потребители. Брандовете трябва да се вслушват и да насърчават активното участие на потребителите, за да печелят доверието им и това да създава резонанс на бранда. Историите са гласът на брандовете, с който да започнат диалога със своите потребители.

Once upon a brand. A brand story is more than content and a narrative. The story goes beyond what’s written in the copy on a website, the text in a brochure or the presentation used to pitch to investors or customers. The story is a complete picture made up of facts, feelings and interpretations, which means that part of the story isn’t even told by the storyteller. Creating a brand story is not simply about standing out and getting noticed. It’s about building something that people care about and want to buy into. It’s about framing scarcity and dictating value. It’s about thinking beyond the utility and functionality of products and services and striving for the creation of loyalty and meaningful bonds with customers.

At current commoditized and saturated market situation the physical product no longer makes the difference, but consumers demand products that provide experiences and add to their expression of self. Stories are central to consumers’ sense making process (Ardley, 2006: 197), as stories help people link what occurs in their lives in a goal-oriented fashion that provides meaning and purpose (Escalas, 1998: 273). When companies and brands communicate through stories they address the consumers’ emotions and values. Brand stories gradually become synonymous with how consumers define themselves as individuals. (Fog et al., 2010: 17-24) According to Papadatos (2006), storytelling brands are the best and most enduring brands, and she recognizes emotional attachment to a brand as an imperative competitive advantage between products or services. Brands need to communicate based on values, create experiences and clearly illustrate how they make a difference in order to build an emotional bond.

Storytelling and branding both originate from same starting point; emotions and values. A strong brand is built on clearly defined values, and stories can be perceived as value statements. A powerful story communicates the brand values in an understandable way and speaks to consumers’ emotion. (Fog et al., 2010: 17-24, 69)

In branding theory context, Kotler and Pfoertsch (2008: 92) include brand story in the elements of a brand. The other key brand elements are name, logo and a tagline or slogan. The elements serve to identify and differentiate a product or a service, and together they form a crucial building block of brand equity. The elements of storytelling According to Fog et al. (2010: 33-34), a good story consists of four core elements: message, conflict, characters and plot. The elements can be mixed, matched and applied in a variety of ways depending on the context in which the story is told, and the story’s purpose. The message needs to be clearly defined and have a strategic purpose in the brand’s objectives. The message should work as an ideological or moral statement that works as a central theme throughout the story. As per Papadatos (2006), theme usually comprises of three core elements: hardship (the work or journey involved in overcoming obstacles), reciprocity (fair exchange of value) and the defining (life changing) moments. Story is set in motion by a change or a fear that disturbs the harmony. These factors form the basis of conflict and force action to be taken. Conflicts address consumers’ emotional needs to bring order to chaos. Conflict in storytelling is not however negative, but it communicates the storytellers’ values and perceptions of right and wrong to the audience. (Fog et al., 2010: 35-36)

In the beginning of a story, the main character’s life seems to be in balance, until he or she experiences an inciting incident. Conflicts arise which must be overcome to complete the journey and to achieve the desired goal. The character perceives an epiphany, a moment of sudden revelation, in a climatic situation of the story. The ending may include an interpretation of what has happened or reveal future events in the characters life. Feelings of failure and success occur in different phases of the journey. (Woodside & Megehee, 2008)

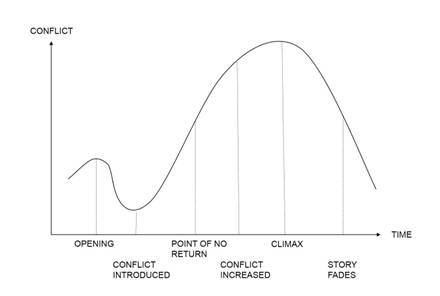

Fog at al. (2010) present a model (Figure 1) which outlines the relationship between the conflict, the character and the flow of events in a story. The Y-axis indicates the conflict development, and the X-axis shows the timeline. A good opening catches the audience’s attention and set the theme and the tone of the story. Next, the progression of change creates a conflict. The conflict escalates to a point of no return and builds up to a climax. The end of the conflict marks the story’s fade out. (Fog et al., 2010: 45).

Figure 1: The story model (Fog et al. 2010: 45)

The story must have characters that the audience is able to associate with. Based on consumers’ need for balance, consumers usually empathize with the character faced with a conflict. Consumers must also be able to understand the motivation behind the characters’ actions. (Fog et al., 2010: 41) Several academics emphasize the persona, often also referred to as the protagonist, as the most important element of the story. According to Herskovitz and Crystal (2010), a good brand starts with a strong, well-drawn and easily recognizable persona that creates a long-lasting emotional bond with the audience. The brand persona drives the continuity for the overall brand message and offers a point of reference that the audience can relate to. The brand persona reflects the audiences understanding of the brands values and behaviors. It can possess recognizable traits, such as imagination, persistence, curiosity or courage, which are tied to a clear intention or purpose. The personas can be portrayed as archetypes. Numerous archetypes have been recognized (Fog et al., 2010; Herskovitz & Crystal, 2010; Woodside & Megehee, 2010), but the most familiar ones include such as:

· the “mentor”, a teacher or a guardian

· the “rebel” who stands up to an authority and breaks the rules

· the “hero” who takes on a journey and goes through a transformation

· the “antihero”, the bad dude

· “mom” who provides nurturing and safety

· the “individualist” who follows his or her own ways

· the “lover” who follows his or her heart and satisfies emotional needs

· the “joker” who entertains others and enjoys life

· the “underdog”, a fighter who takes advantage of the fact that he or she is constantly underestimated (Woodside et al., 2008: 114; Fog et al, 2010: 94; Herskovitz & Crystal, 2010: 22)

When people are able to relate to the character’s thoughts and feelings and observe personal development, they are more likely to be drawn to the story. A narrative in which the protagonist’s situation rapidly improves or worsens, or alternates between the two, is suggested to be especially good at generating emotional responses in consumers. (Escalas, 1998: 280) According to Herskovitz and Crystal (2010), people naturally connect and identify with a persona which is believable and consistent, and whose actions and words match. But while a good persona remains true to its core, it is also able to evolve with time and with changing situations. “As this happens, good brands come to evoke strong emotional responses from their customers, including trust, loyalty, and even devotion” (Herskovitz & Crystal, 2010: 24). Also as per Fog et al. (2010: 167) a good story evolves over time as the characters develop their personality, and the audience gets to know them better. If the characters are well known, the audience is more likely to embrace the story. Some companies have developed a story that is mainly based on their customer promise. These stories often speak about the company’s character and may personify this through their founders. In each case, the status and respect of the company is enhanced by the exploits of and stories told by its representatives. (Dowling, 2006: 92)

Fourth element, the plot, is vital for the consumers’ experience. Story only exists as a progression of events, and as a sequence of actions. The difference between the concepts of story and plot are often misunderstood, but as a story is a narrative of events in a linear time-sequence, a plot emphasizes the sense of causality internal to the time-sequence (Stern, 1994: 603). Escalas (1998: 268) emphasizes chronology and causality as the two most important elements of a story. As per Papadatos (2006), the plot conveys the story’s theme, and comprises of following four elements: anticipation (sense of hope for the future), crisis (conflict or despair), help along the way (minor or major miracle) and the goal achieved (sense of accomplishment and satisfaction). Several academics have attempted to create a universal categorization of plots (Brown & Patterson, 2010: 544). For example, Frey’s four categories of mythic plots derived from literature, but have since been applied to advertising appeals and consumption narratives (Stern, 1995: 165). Frye’s categories are comedy, romance, tragedy and irony. Gabriel’s (2000) four story types are epic, comic, tragic and romantic, strongly resembling the categories of Frey. Booker (2004) has presented seven archetypal master plots that according to him recur in all storytelling. The plots are referred to as rags to riches, rebirth, the quest, overcoming the monster, tragedy, comedy, and voyage and return. Stories can be divided into seven different types with an emphasis on stories in a digital environment. The most impactful stories are the ones that contain more than one master plot, and the more master plots they contain the more impactful the stories are (Brown & Patterson, 2010: 544). Chiu et al. (2012) have studied previous literature on brand story elements and identified four characteristics that contribute to a good brand story. These elements are generally useful in engaging audience in evaluations of a product or service and strengthening their related feelings, in order to create positive correlations with brand attitude and purchase intention. The elements are:

· authenticity, which is associated with genuineness, truthfulness and originality

· conciseness, which reduces boredom and tedium from the story by excluding unnecessary words, phrases or details

· reversal, which helps consumers to recognize problem-solving capabilities and implies actions to take;

· humor, which increases brand liking and possibly consumers’ comprehension of the message. (Chiu et al., 2012)

In modern society, marketing creates tension between authenticity and inauthenticity. A more authentic brand story provides consumers with credible information which helps them acquire understanding of the product or service, and help them to judge it. In addition, when consumer perceives authenticity, he or she feels more connected with the story. As per Guber (2007: 55), authenticity is crucial to the success of a story and good storytelling is built on integrity. Authenticity does not however mean that stories need to be based on truth – they can be fact of fiction – but the relationship between the brand and the story needs to be authentic (Lundqvist et al., 2013: 286). In a fictional story, the company is however ethically bound to ensure that the audience is not misled in this respect (Fog et al., 2010: 173).

Busselle and Bilanzic (2008) actually propose that the most engaging stories often are both fictional and realistic, and it is the engagement factor of the story that leaves consumers with a sense of authenticity. Only if consumers observe inconsistency in a story, they start to suspect its realism and authenticity. When communicating with customers, companies should get the main message across concisely, as people neither have the time nor the patience to absorb an overly detailed story (Chiu et al., 2012). The conciseness could be associated with simplicity. Adamson (2008: 92) endorses that the brand message must capture the essence of a brand’s relevantly different brand promise to customers. In an environment filled with different brand touchpoints on many different dimensions, the importance of making the central idea or message as simple as possible and as memorable as possible has become magnified. Reversal story reveals the best way to solve problems or obstacles, which implies the action that consumer should take if faced with the same challenge. According to the authors, a positive ending of a story may create positive affect and induce greater liking than an ending that is not clearly resolved. Guber (2007) states that the audiences’ emotional response is especially important what comes to the ending of the story; it is the first thing that the audience remembers. He however emphasizes that although the story should be emotionally fulfilling, it does not always mean the same as a happy ending (Guber, 2007: 57).

Chiu et al. (2012) suggest that humor increases the transfer of positive affect for a product or service, and enhances consumers’ cognitive responses. Viewing humorous messages increases audience’s attention and thus the possibility of their comprehension of the message. Humorous stories have the highest retention levels, and they are more easily absorbed by the audience (Dahlen et al., 2010: 342). However, as most products or services are not humorous by nature, humor should only function as a marginal element as opposed to the main message argument. Also, as humor is a difficult talent to master, a misunderstood joke can cause the audience to feel threatened or insulted (Dahlen et al., 2010: 343). Humor is however consistently found to be an effective way to catch audiences’ attention, and research shows it generates positive affect and appreciation. (Kuilenburg et al., 2011; Chiu et al.,2012)

Although, we presented several essential elements of storytelling, there is no universal agreement of a story’s structure. Some academics emphasize the sequential order of actions, whereas others emphasize the purpose or intention of the protagonist. While theories about the necessary elements vary, they consistently agree on the necessity of chronology and causality. That is, a story must contain a recognizable time-dimension, and there must exist a defined relationship between the story’s elements. (Escalas, 1998)

As stated previously by Kotler and Pfoertsch (2008), a brand story is a distinctive branding element which serves as a creator of brand equity. The first stage of brand equity, brand awareness, references brand recall, brand recognition and top-of-mind as levels of brand salience. According to Dowling (2006: 83), all company communication is designed to raise awareness. As per academics, stories serve as a fundamental aid to memory and assist individuals to remember important things (Ardley, 2006; Herskovitz & Crystal, 2010). Herskovitz and Crystal (2010) especially emphasize a well-defined brand persona as an instantly recognizable and memorable element of a brand story. Love (2008: 24) implies that stories are “sticky”, and if a company’s message is demonstrated through a simple, compelling and emotionally engaging narrative, the ability of the audience to recall the message will be much higher than if presented via non-narrative communication. She cites a study by London Business School, which illustrates that narrative messages have a retention rate between sixty-five to seventy percent, whereas only five to ten percent retention rate was achieved when solely traditional communication methods were used.

Marzec (2007) provides a deeper scientific understanding in what makes stories memorable and effective. He suggests that at most fundamental level, people learn through stories, and that neuroscientists have uncovered that three actions of human brains – processing, retaining and recalling of information – are all aided and enabled by storytelling. Humans’ memory capacity can better manage information if it is inter-related. The story-format provides a framework to demonstrate the connections between different elements and concepts, and thus works as a natural mental organizing device. Woodside and Megehee (2010: 419) also support the view that human memory is story-based. Information is indexed, stored, and retrieved in the form of stories. A story can cause implicit or explicit awareness and emotional connection and understanding in the minds of the audience.

The second element of brand equity, brand associations, represent what the brand stands for, and how it can be differentiated from the other brands of the same category. Brand associations, which can be formed from consumers’ functional, emotional or self-expressive needs, form a basis for brand identity. Brand identity should help establish a relationship between the brand and the customer by generating a unique value proposition. Padgett and Allen (1997) suggest that advertising should aim at communicating both functional and symbolic meanings, and highlight that narrative form has several benefits as a conceptual foundation for advertising and building of brand image. The authors separate ads into two types; narrative ads which present a chronological series of events acted out by a character, and argumentative ads which present logically connected ideas not enacted by a character. The authors’ findings indicate that the strength of argumentative ads is the conveyance of functional product or service attributes, but their weakness is the lack of information that would stimulate symbolic responses and thus build brand image. In contrast, the narrative ads present stories, demonstrate thoughts, feelings and behaviors and prompt consumers to construct symbolic meanings to interpret the advertisement. The narrative ad rather demonstrates than explains the functional elements of a product or service, and as such allows consumers to construct their own meanings and associations. The authors however notify that as narrative ad can generate a variety of associations between consumers, it can possibly increase the ambiguity of the brand image rather than strengthen it. To avoid that possibility, companies need to present narrative ads with similar structures that elicit the same theme. Thematic consistency is essential for the creation of consistent brand image. (Padgett & Allen, 1997)

A good brand story builds product knowledge and positive emotion, and allows the company to highlight its differences and reduce consumers’ price sensitivities. Understanding of the brand and the positive emotions should imply a solution to consumers’ needs and as a consequence create a positive brand attitude and purchase intentions. (Chiu et al., 2012: 272)

Stories help consumers to understand the benefits of a brand, and add favorable and unique associations to a brand. Such associations can lead to an understanding of points-ofdifference and increase customer-based brand equity. Brand stories can convey positive features of a product or service without being perceived as an actual commercial. A research conducted by Lundqvist et al. demonstrates that brand stories can be used to create and reinforce positive brand associations with a brand and increase the consumers’ favorability with the brand. The authors suggest that stories offer a way to differentiate the brand by adding an emotional connection, which is difficult for competitors to match. The emotional connection cannot be achieved through attribute-oriented benefits, but can only be created by appealing to consumers’ dreams and aspirations.

Below model (Figure 2) indicates the development of brand equity assets from the perceived product or service attributes to brand value. (Lundqvist et al., 2013)

Figure 2. The effect of storytelling on brand value (adapted from Lundqvist et al. 2013: 293)

The third asset of brand equity is the perceived quality of the product or service, and the positive brand responses derived from the consumers’ opinions, evaluations and emotions. According to Baker and Boyle (2009: 83) stories speak to both parts of the human mind, reason and emotion, but when something is felt, it is more likely to be shared with others. An emotional response is a binding force that can be achieved through appealing to the audiences’ senses and emotions. Through an effective emotional response, a company can transfer consumers into ambassadors of the brand (Guber,2007: 57).

Escalas (2007) has proven that by structuring an ad as a narrative – including the basic elements of a story such as a plot and a character – the message can be more persuasive than an analytical illustration of a product’s features. Also Padgett and Allen (1997) suggest that narrative ads are more likely to be successful than argumentative ads. With argumentative ads, consumers are more likely to create counterarguments. Chiu et al. (2012: 266) suggest that one of the key elements of a brand story, humor, not only increases the transfer of positive affect for a product or service, but also enhances the customer cognitive process and helps understand product benefits. According to the authors’ findings, a reversal story – that is a story that describes other consumers’ similar problems and provides surrogate experience information – can elicit high levels of positive emotional responses. Love (2008:24) supports the notion of humor; according to her a good story allows the audience to form an emotional connection which can be magnified by a dash of humor and selfdeprecation. As per Fog et al. (2010), information in stories is packaged into a meaningful context, making it easier for the audience to understand the depth and relevance of the information.

Scientists believe that stories stimulate the use of both the logical and creative parts of the brain at the same time, meaning that the information is understood factually as well as visually and emotionally. (Fog et al., 2010: 153) The highest level of brand equity is brand resonance, which indicates the degree of commitment that the brand has achieved, and in which brand relationships are characterized by loyalty. Keller (2009) identifies active engagement – the willingness to invest personal resources to a brand – as an aspect of brand loyalty. Sheehan and Morrison (2009) exclaim that the traditional “mass message” model of advertising fails to recognize the importance of one-to-one engagement and interactivity. The authors see that people are inherently social and look to create and maintain relations not only with other people but also with brands. Brand stories provide ways for companies to engage more deeply with brands. From an interactional engagement perspective the brand story becomes part of a person’s own story about him - of herself. (Sheehan & Morriso, 2009: 41)

Baker and Boyle (2009) draw an example from the great leaders like Martin Luther King Jr., Gandhi or Churchill, who used storytelling to paint a compelling vision of the future and shaped the way how people saw the world. By sharing their stories, the leaders made their audience more committed into making those stories real. According to Baker and Boyle, a good story needs to be shared, so that people can be engaged by the story and in doing so, compelled to make it their own. Storytelling is a shared experience among equals in which the audience is just as active participant as the storyteller. When people are entrusted to construct their own meanings from the story, they will become more committed to the story. (Baker & Boyle, 2009)

Herskovitz and Crystal (2010) see the brand persona as a central creator of long-lasting relationship between the brand and the customers. Loyalty and trust are built over time as a result of hundreds or thousands of wellpreformed acts, and if the brand’s message and actions match, they can assist to create an intrinsic and implicit emotional connection based on the predictability of the brand’s behavior. (Herskovitz & Crystal, 2010)

Sevin and White (2011) believe that storytelling is a feasible communication method to catch relevancy and encourage engagement in the audience, and 46 that branding projects should make use of real-life stories to be more relevant and engaging than traditional advertising campaigns for their audience. Writers agree with Herskovitz and Crystal (2010) that it is possible to establish a strong emotional bond between the brand and the audience through personal narratives and stories. (Sevin & White, 2011) The research conducted by Lindqvist et al. (2013) proves that consumers who have been exposed to a brand story, are more likely to respond positively to the brand. The authors present a graph which describes how the brand is experienced through the story and how the brand experience leads to brand value. Lindqvist et al. propose that due its relationship-building elements, storytelling is also suitable for customer to customer marketing. An effective story engages consumers to become ambassadors of the brand, spreading positive word-of-mouth and giving out positive recommendations. (Lindqvist et al., 2013) Adamson (2008) presents an insight from Smirnoff vodka’s Senior Vice President of Marketing, Philip Gladman. Smirnoff utilizes both traditional channels of marketing and social media platforms to promote the “unique Smirnoff way”. As per Gladman: “People don’t bond with the vodka because of how it’s made. They bond with it because of its back story. The intent of our branding is to get people engaged in this story as a way to gain understanding of what makes our brand of vodka authentically different.”(Adamson 2008, 244)

Social media consists of a variety of new sources of online information, including social networking sites (such as Facebook, Instagram, Google+,LinkedIn), social content sites (YouTube, Flickr, wiki), microblogs (including Twitter), social recommendation sites (Pinterest) and social bookmarking sites (Google Maps). The sudden growth of social media’s popularity suggests almost primal appeal. It is fundamental human behavior to seek identity and “connectedness” through affiliations with other individuals and groups that share their characteristics, interests or beliefs (McKinsey Global Institute 2012).

The new media provides immense opportunities for storytelling for both companies as well as consumers. According to Adamson (2008: 18), the role of storytelling in company’s brand building has been reinforced by digital technology. Through social media, consumers are brought together, and are able to share their opinions and experiences regardless of time and place. Anybody with an access to the internet can assume the role of a storyteller and have an influence on global audience. Companies can try to establish a dialogue in social media in which customers can actively contribute to the making of the brand – adding credibility and substance to the content. The modern culture is highly characterized by participation, interaction and dialogue, and companies’ must take a careful look of their chosen communication strategies. (Fog et al., 2010: 184-188)

Today’s brands are open books where there is no single author of the brand story. Although a company can try to create a story on their own, it is up to the consumers to embrace, alter or reject the brand’s message. Digital technologies have greatly enhanced the consumers’ control in brand building. A brand story should be written collaboratively between the brand and the consumer in an on-going process. Brands need to listen and encourage active participation in order to gain the consumers’ trust and create brand resonance. Companies should not fear the loss of control in regard to its brand because of social media, but fully engage in the opportunities the new technologies have to offer and tap into its power (Waters & Jone, 2011: 252). Companies must take more of a controlling interest in what consumers experience and the stories they share online. The technological tools and the behaviors that consumer responses stimulate enable companies to get better information about customers, to reach consumers exactly when and how they would like to be reached, and to deliver products and services that have been improved based on the received input. (Adamson, 2008)

In the social media era, companies must earn the customers’ attention, and achieve it by connecting profoundly to the consumers’ aspirations and desires. Social media sites are eminently suitable in telling stories and engaging consumers, and storytelling is a powerful means to build lasting relationships with the customers. Companies are taking storytelling tactics seriously, and re-inventing their branding strategies and materials accordingly. The examples for storytelling practices in social media platforms are endless. Coca-cola adopted a new approach to its website in 2012, creating a “Coca-Cola Journey”. The content has an emphasis on storytelling around the world, and it aims at engaging consumers and all other stakeholders in a meaningful way. According to Coca-Cola’s director of digital connections and social media, Ashley Brown: "We're now stitching everything together: Twitter, YouTube, Google+, LinkedIn. Over the last four months our tweets, for instance, have become not about 'broadcasting' but engaging, and driving to real content that inspires”. (Elliott, 2012)

Social media endeavors, that involve user-generated content and characters of interactive storytelling, are very likely to generate commitment on the part of the consumer, reinforcing loyalty to the brand and making the consumer more likely to commit additional effort to the brand in the future. Once the consumers are engaged, they are in a position to communicate their opinions to other consumers. Satisfied and loyal consumers communicate their positive attitudes towards the brand itself or towards a new group of consumers, online or offline. Dissatisfied consumers may also share their negative attitudes, and companies must be proactive or reactive in this regard. (Hoffman, 2010)

Sheehan and Morrison (2009) have created a concept “confluence culture”, where traditional advertising must adapt to embrace the new reality of interactive content, emerging media and changed media production and consumption methods. The authors recognize that many online users are not content with accessing and viewing content from established sources, but want to interact with message content by adding to it or repurposing it for new or different uses. In order to succeed in the “confluence culture”, companies must move towards providing content for consumers to create their own stories, by taking the information provided about the brands and mixing it with their own experiences. “Participation, remediation, collective intelligence, and bricolage encourage the development of many more messages, allow many more stories to be told, and enable users to become much more involved with the brands than ever before”. Sheehan and Morrison believe that strong brand stories are a key element of social media, which can result in compelling characters that represent the brand and with which consumers are very likely willing to engage with long-term. (Sheehan & Morrison, 2009)

Fundamental issue for companies is how to communicate the story forward. Companies struggle to tell their stories cost-effectively to as wide audience as possible (Dowling, 2006). The current technology changes the way consumers receive messages, and the messages disseminated through social media platforms should consider specific peculiarities of the new technology, such as the ability to create and interact with information. Oneway communication methods are no longer effective but individuals should be given an active role in the communications process. With the use of modern technologies, stories are transmitted in timely manner and target audiences have the option to both tell their stories and to interact with the stories of other individuals. The motivation of consumers to tell brand stories comes from the desire to share ideas and experiences as an advocate of the brand. (Sevin & Whit, 2011)

Quek (2012) considers that it is not up to the selection of the medium which determines a story’s success, but the story’s content. The selection of the medium is important only in its speed – how fast the content is shared, and how identical the shares are to the original source. The content has to be unpredictable, aim to surprise and be unanticipated by its audience. Quek’s notion is academically supported by Escalas (1998: 280), who believes that stories should not confirm too rigidly to expectations, but include an element of novelty. Quek notes that the most contagious content are photos and videos; videos are shared twelve times more than links and posts combined in Facebook. Storytelling can be utilized for creation of brand equity, and that storytelling has reached new dimensions in the modern technological environment.

REFERENCES

1.Adamson, A. P. 2008. Brand digital: simple ways top brands succeed in the digital world. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. Ardley, B. 2006. Telling stories about strategies: a narratological approach to marketing planning. The Marketing Review, 6 (3): 197-209.

2.Ardley, B. 2006. Telling stories about strategies: a narratological approach to marketing planning. The Marketing Review, 6 (3): 197-209.

3.Baker, B. & Boyle, C. 2009. The timeless power of storytelling. Journal of Sponsorship, 3 (1): 79-87. Barwise, P. & Meehan, S. 2010. The one thing you must get right when building a brand. Harvard Business Review, 88 (12): 80-84.

4.Booker, C. 2004. The seven basic plots: why we tell stories. London: Continuum.

5.Brown, S. & Patterson, A. 2010. Selling stories: Harry Potter and the marketing plot. Psychology & Marketing, 27 (6): 541-556.

6.Busselle, R. & Bilandzic, H. 2008. Fictionality and perceived realism in experiencing stories: a model of narrative comprehension and engagement. Communication Theory, 18 (2): 255-280.

7.Chiu, H-C., Hsieh, Y-C. & Kuo, Y-C. 2012. How to align your brand stories with your products. Journal of retailing, 88 (2): 262-275.

8.Dahlen, M., Lange, F. & Smith, T. 2010. Marketing communications: a brand narrative approach. Chichester: Wiley. Denning, S. 2006. Effective storytelling: strategic business narrative techniques. Strategy & Leadership, 34 (1): 42-48.

9.Dowling, G. R. 2006. Communicating corporate reputation through stories. California Management Review, 49 (1): 82-100.

10. Elliott, S. 2012. Coke revamps web site to tell its story. NY Times 12.11.2012, http://www.nytimes.com/2012/11/12/business/media/coke-revamps-web-site-to-tell-its-story.html?_r=0 (Accessed 10.11.2016).

11. Escalas, J. E. 1998. Advertising narratives: what are they and how do they work? In Stern, B. B. (Eds), Representing consumers: voices, views and visions. London: Routledge. 92

12. Escalas, J. E. 2007. Self-referencing and persuasion: Narrative transportation versus analytical elaboration. Journal of Consumer Research, 33 (4): 421-429.

13. Fog, K., Budtz, C., Munch, P. & Blanchette, S. 2010. Storytelling: branding in practice. 2nd edition. Branding in Practice. Berlin: Springer.

14. Gabriel, Y. 2000. Storytelling in organizations: facts, fictions, and fantasies. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

15. Guber, P. 2007. The four truths of the storyteller. Harvard Business Review, 85 (12): 52-29.

16. Herskovitz, S. & Crystal, M. 2010. The essential brand persona: storytelling and branding. Journal of Business Strategy, 31 (3): 21-28.

17. Hoffman, D. L. & Fodor, M. 2010. Can you measure the ROI of your social media marketing? MIT Sloan Management Review, 52 (1): 40-49. 93

18. Keller, K. L. 2009. Building strong brands in a modern marketing communications environment. Journal of Marketing Communications, 15 (2- 3): 139-155. 94

19. Kotler, P. & Pfoertsch, W. 2008. B2B Brand Management. Berlin: Springer.

20. van Kuilenburg, P., de Jong, M. D. T. & van Rompay, T. J. L. 2011. “That was funny, but what was the brand again?” Humorous television commercials and brand linkage. International Journal of Advertising, 30 (5): 795-814.

21. Love, H. 2008. Unraveling the technique of storytelling. Strategic Communication Management, 12 (4): 24-27.

22. Lundqvist, A., Liljander, V., Gummerus, J. & van Riel, A. 2013. The impact of storytelling on the consumer brand experience: The case of a firmoriginated story. Journal of Brand Management, 20 (4): 283-297. 95

23. Marzec, M. 2007. Telling the corporate story: vision into action. Journal of Business Strategy, 28 (1): 26-36.

24. McKinsey Global Institute. 2012. The social economy: Unlocking value and productivity through social technologies. The executive summary. (online) Available at: http://www.mckinsey.com/insights/mgi/research/technology_and_innovatio n/the_social_economy> (Accessed 4.11.2016).

25. Padgett, D. & Allen, D. 1997. Communicating experiences: A narrative approach to creating service brand image. Journal of Advertising, 26 (4): 49-62.

26. Papadatos, C. 2006. The art of storytelling: how loyalty marketers can build emotional connections to their brands. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 23 (7): 382-384.

27. Quek, C. 2012. 3 ways to tell a social brand story. Huffington Post 19.10.2012,

http://www.huffingtonpost.com/christel-quek/social-branding_b_1971349.html (Accessed 11.11.2016).

28. Sevin, E. & White, G. S. 2011. Turkayfe.org: share your türksperience. Journal of Place Management and Development, 4 (1): 80-92.

29. Sheehan, K. B. & Morrison, D. K. 2009. The creativity challenge: media confluence and its effects on the evolving advertising industry. Journal of Interactive Advertising, 9 (2): 40-43.

30. Stern, B. B. 1994. Classical and vignette television advertising dramas: Structural models, formal analysis and consumer effects. Journal of Consumer Research, 20 (4): 601-615.

31. Stern, B. B. 1995. Consumer myths: Frye’s taxonomy and the structural analysis of consumption text. Journal of Consumer Research, 22 (2): 165- 185.

32. Waters, R. D. & Jones, P. M. 2011. Using video to build an organization’s identity and brand: A content analysis of nonprofit organizations’ YouTube videos. Journal of Nonprofit & Public Sector Marketing, 23 (3): 248-268.

33. Woodside A. G. & Megehee, C. M. 2010. Advancing consumer behaviour theory in tourism via visual narrative art. International Journal of Tourism Research, 12 (5): 418-431.