The symbol S in syntactic theory

1. The sentence as a basic structural unit and the phenomenon of recursion.

In modern syntactic theory, it is the sentence, not the word, that is almost generally accepted as the primary structural unit. In early and ‘standard’ generative syntax, the activation of S as a root symbol started the process of generation of the syntactic structure. The process was supported by a finite set of rewrite rules:

(1) S -> NP VP

NP -> Det (Adj*) N (PP)

VP -> V (NP) (PP)

etc.

Some symbols could be used more than once in the process of generation. Further, the same symbol could appear both to the left and to the right of a rewrite rule:

(2) NP -> Det (Adj) N

After lexical insertion, (2) could yield. e.g., the phrase ‘these leather shoes’.

Recursion was defined as an important feature of language, allowing the generation of an infinite number of sentences with a finite set of resources. It could be applied very early in the derivation to yield rules of the type:

(3) S -> S*,

as in ‘John was singing and Mary was dancing’.

This same symbol S could be used lower in the derivation – to the right of V in the rule rewriting VP, to the right of N or even instead of it in the rules rewriting NP:

(4) VP -> V S

(5) NP -> Det N S

(6) NP -> S,

as in ‘[I]gathered she was bored’. ‘the girl who was bored’ or Whoever is bored [is a nut], respectively.

The same symbol S was thus used to refer to the root sentence, to conjunctively linked clauses and to subordinate clauses in different syntactic function – the implication being that anything qualifying as S can appear as a substitute of S in any of the S-positions.

In the years following the appearance of N. Chomsky’s “Remarks on Nominalisation” (Chomsky 1970), R. Jackendoff’s X-bar syntax (Jackendoff 1977) and work on functional superstructure, different varieties of S appeared. The symbol was initially split into S’ (Complementiser + S) and S. For Bulgarian, some authors subdivided S’ into ‘че-’ (that-) clauses and ‘да-’ (to-) clauses, assuming Complementiser status for both the conjunction and the particle (Cf. Penchev 1993, 1998). S itself appeared in different flavours: tensed or untensed, V-endowed or ‘small’. It finally disappeared from syntactic notation, leaving plenty of room for AGRPs or TPs or ThPs and less room for Recursion.

While the process of S-differentiation was a long and sinewy one in generative work, the issue of S-recursion appears as an immediately observable problem in the course of analysis of even a small-sized Bulgarian treebank. In what follows, I present the application of such a treebank in the construction of formal models and the validation of linguistic hypotheses

2. Treebanks in theory construction and validation.

The long-standing debate between rationalist and empirical approaches to language study has recently been resolved with the creation of a third, ‘hybrid’ approach. This integration was not unexpected: more than twenty years ago, G. Leech ( Leech 1987) saw it as a bidirectional process. On the one hand, he held, research in artificial intelligence would seek to enlarge its empirical basis and improve its descriptive adequacy; on the other hand, the corpus linguistics paradigm would opt for greater precision and analytical depth (Cf. Leech op. cit.:3). Treebanks, offering an environment for presentation of text corpora in pre-defined structure, are one clear example of the coming together of the two approaches. J. Aarts described one possible application of treebanks in theory construction as a cyclic process of hypothesizing, verification and correction. The input to the environment is a ‘competence’-type grammar, to which a corpus is fed. This confrontation inevitably demonstrates inaccuracies and areas of inadequacy in the input formalism. The output is, again, a ‘competence’ grammar, but enriched with (and improved by) observations of performance. (Cf. Aarts 1991: 47)

TREE – the environment used to derive the data presented in this paper – was created in the early 90es at the Laboratory of Linguistic Modelling of the Bulgarian Academy of Sciences as part of the larger project: “A Linguist’s Workbench” (Cf. Note 1). The environment does not limit the user with respect to the choice of formalism of syntactic presentation. It allows easy mapping from one structure to another, thus supporting, if necessary, the encoding of syntactic movement. At the stage of search, TREE allows the following modes: a/ search for a string of syntactic symbols (e.g. all strings of the type V PP), 2/ search for symbol substitutes, yielding all the strings in the corpus appearing under a marked symbol.

The ‘input’ formalism is a context-free grammar with a two-level syntactic hierarchy of categories. Functional superstructure was not part of the first cycle grammar and input annotation.

The corpus annotated and analysed with TREE consists of two short stories by the Bulgarian writer Elin Pelin(Cf. Note 2).

3. Rewriting S.

3.1.The ‘Sentence Front’

The top-down querying of the Treebank yields as a first result the following rewrite rules, containing the symbol S both to the left and to the right of the arrow:

(7) S -> Conj S

S -> AdvP S

S -> PP S

S -> NP S

S -> S’ (= CP) S

In what follows, the rules in (1) will be consecutively exemplified. Their adequacy when confronted with the corpus data will be tested and discussed.

3.1.1. Rewriting S as CONJ S

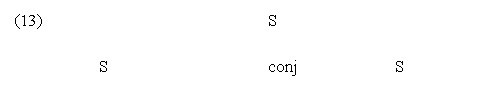

A typical example of the recursive insertion of S under the root S-symbol, with potentially unlimited possibilities for recursion, is the rule defined in early generative grammar as ‘S -> S CONJ S’.

In the Treebank (further: TB), the following conjunctions appear in the position CONJ: и [‘i’ – and], или [‘ili’ – or], но [‘no’ – but], а [‘a’ – but, and], ‘zero’, marked with a comma.

At first glance, the data confirm the recursive application of the rule, displaying structures with more than two conjunctively linked clauses. In the TB, these are at most three, conjoined as follows:

- with more than one ‘zero’ conjunction:

(8) Пот се сипе от челата, душата без сили остава, няма почивка.

Sweat refl.-cl. drips from foreheads-the, soul-the without force remains, not-have (Impersonal) rest.

Sweat drips from the foreheads, the soul remains without force, there is no rest.

- a first zero conjunct, followed by и [i – ‘and’]:

(9) Изправя се старата му майка, усмихва му се с любов и като зажъна, рече:

Straighten refl.-cl. old-the his-gen.-cl. mother, smile to- him-dat.- cl. refl.-cl. with love and as start-reaping-ed1, said:

His old mother straightened herself up, smiled to him with love and, starting to reap, said:

- и [i], followed by но [no – ‘but’]:

(10) – У-у, извика весело Пенка и се спусна да ги бере, но отведнъж побягна.

– Uh-uh, shouted gaily Penka and refl.-cl. rushed to them- acc.-cl. pick, but suddenly ran away.

– Uh-uh, gaily shouted Penka and rushed to pick them, but all of a sudden ran away.

The definition of the exact syntactic position of the ‘CONJ’ node is a problem which might seem trivial; however, its elaboration proves to be enlightening on a number of general problems of structure. Below, I turn to the structure of conjoined phrases in the context of the principle of binarity.

Defining conjunctive linking in Bulgarian, Penchev 1993 presents it as follows:

(11) XP -> XP {C/,} XP,

where X can be any category, including S, ‘C’ is a phonetically non-null conjunction, and ‘,’ is meant to stand for a ‘zero’ conjunction.

In the above-cited work, I. Penchev proposes the following analysis of conjunctively linked sentences:

(12) Студентите са пред дворeца и учениците са пред двореца:

Students-the are in-front-of palace-the and pupils-the are in-front-of palace-the.

The students are in front of the palace and the pupils are in front of the palace.

Студентите са пред двореца и учениците са пред двореца,

where the position of the conjunction is assumed to be between the two clauses.

The problems discussed below relate to the binary or non-binary character of the conjunction rule; to the degree of parallelism between the root-sentence and the clause; to the applicability of recursion rules in the case of S.

The adequacy of the non-binary structure ‘S CONJ S’ (and probably, in general, ‘X CONJ X’) is questioned by two groups of data in the Bulgarian TB, one of these providing arguments of a general nature and the other – language-specific arguments:

1/ Sentence conjunctions and the possibility to generalize over S-sentence and S-clause conjunction rules and 2/ Conjunctions and the pseudo-second position of clitics.

S-conjunction

Apart from being a connective between two clauses and in spite of the recommendations of most prescriptive grammars, conjunctions very frequently appear in sentence-initial position, as an inter-sentence link. In the TB, this fact is presented with data exemplifying the string ‘CONJ S’. The most frequent inter-sentence conjunction is и (‘i’ - and), but а (‘a’ – while) and но (‘no’ – but) can also appear in this position.

(14) И ето че някъде далече се поде самичък глас.

And lo that somewhere far refl.-cl. make-oneself-heard lonely voice.

And here comes, from far-away, a lonely voice.

(15) И прижуреното й пълно личице светна от усмивка.

And burned-the her-gen.-cl. full face-diminutive lit up from smile.

And her full burnt up face lit up with a smile.

(16) А песента се ширеше, волна и млада.

And song-the refl.-cl. carried, free and young.

And the song carried at will, free and young.

(17) Но ето че дотича из oтдалеченото краище босоного хлапе.

But lo and ran-up from far-the region barefooted boy.

But lo, and from the distant region ran up a barefooted boy.

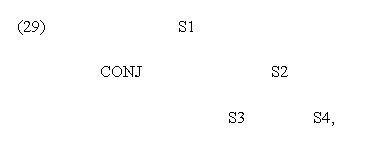

If the rule S -> S CONJ S is replaced by two rules, S -> (CONJ) S and S -> S*, the consecutive application of these rules will allow the generation of strings of the type:

(18) S -> (CONJ) CONJ S CONJ S.

The legitimacy of this string finds confirmation in the TB, which contains a number of sentences with a sentence-initial conjunct, followed by one of two correlative conjunctions heading the clauses – Cf. (13):

(19) И ту развълнувано глъхнеше, ту смeло се вдигаше (…),

And now excitedly died away, now bravely refl.-cl. rose.

And it would now die away with excitement, now bravely rise up (…),

where the inter-sentence conjunction forms part of a sentence containing two clauses, each headed by a correlative conjunction.

The data also indicate, however, an asymmetry between the two types of S, i.e. S-sentence and S-clause: the sets of possible sentence-conjunctions and clause-conjunctions are not identical. One obvious example is that correlative conjunctions only apply at the clausal level.

Adopting a binary structure rule for conjunctive linking yields a descriptively no less adequate result than the rule S -> S CONJ S, but has two advantages: the possibility to generalise over two types of rules and, on a more general plane, the possibility to apply the principle of binarity in the construction of syntactic trees. The data also indicate that better descriptive adequacy can be achieved if the categories ‘root S-sentence’ (further: S1) and (each conjoined) ‘S-clause’ (further: S2) are set apart.

The second group of examples illustrates the connection between the position CONJ and the appearance of clitics.

CONJ and the pseudo-second clitic position.

In Modern Literary Bulgarian, a clitic cannot appear as the first phonetically non-null element of a sentence – a rule, also established for other languages and known as ‘Wackernagel’s Law’ (Cf. Wackernagel 1892). To put it simply, a Bulgarian sentence cannot start with a clitic. Now, the non-binary rule ‘S -> S CONJ S’, where ‘CONJ’ does not form part of the clause, cannot explain the grammaticality of the following strings:

(20) (…) полека-лека се засили и се залюля на мощни вълни над полето.

by-and-by refl.-cl. got-stronger and refl.-cl. swung in powerful waves over field-the.

gradually it gained strength and swung in powerful waves over the field.

(21) Не изтърпя Никола, а се изстъпи сред нивата и се провикна

Not bear Nikola but refl.-cl. came forward in field-the and refl.-cl. cried out.

Nikola could bear no longer, but stepped forward in the middle of the field and cried out.

(22) – У-у – извика весело Пенка и се спусна да ги бере.

– Uh-uh – cried gaily Penka and refl.-cl. ran to them-cl. pick.

– Uh-uh – gaily cried Penka and ran to pick them.

(23) Майка й вдигна очи и я погледна спокойно.

Mother her-cl. raised eyes and her-cl. looked over calmly

Her mother raised her eyes and looked at her calmly.

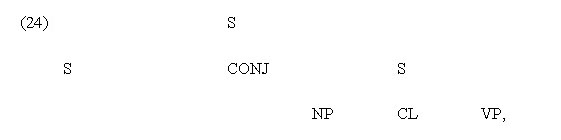

The syntactic structure has the following form:

with a zero-realization of NP. As demonstrated by the construed versions of (23) below, a null realisation of CONJ leads to ungrammaticality:

(25) *Майка й вдигна очи, я погледна спокойно.

Mother her-cl. raised eyes, her-cl. looked calmly.

Her mother raised her eyes and looked at her calmly.

(26) *И майката прегърна Пенка, я помилва по хубавото лице.

And mother-the embraced Penka, her-cl. caressed on beautiful-the face.

And the mother embraced Penka, caressed her beautiful face.

The behaviour of clitics in the conjunctively linked clauses, as observed in the TB, can be formally described and explained if a binary structure with an initial ‘CONJ’ position in the phrase is adopted.

On the other hand, a clause-first clitic within a non-initial clause is admissible in cases where the two clauses are not conjunctively linked – as in (28) below, where the movement of the subordinated adverbial clause to the sentence front leaves a clause-initial position for the clitic, but – nevertheless – a grammatical structure:

(27) *Се люлеят златни ниви, докъде ти око види.

Refl.-cl. swing golden fields, upto-where your-cl. eye sees.

Golden fields are swaying, as far as the eye can see.

(28) Докъде ти око види, се люлеят златни ниви.

Upto-where your-cl. eye sees, refl.-cl. swing golden fields.

As far as the eye can see, golden fields are swaying.

The grammaticality of (28) and the need to formulate formal rules to account for it speaks in favour of distinguishing between S2, on the one hand, and S3 and S4 (the main clause and the subordinate clause) as structures having different status.

The comparison of the first cycle grammar rules with the TB data thus seems to indicate the necessity to reformulate (24) as (29):

where S3 is a main clause and S4 – a subordinate. The status and structure of these two clauses remains to be elaborated.

3.1.2. Rewriting S as ADVP S

To a very few exceptions, adverbial S-adjuncts take up a position at the head of the sentence, preceding the subject or a pronominal clitic:

(30) Сега му шие риза.

Now him-dat.-cl. zero-subject sew shirt.

She is now sewing a shirt for him.

(31) Вчера се получи писмо от него.

Yesterday passice.-cl. received letter from him.

Yesterday a letter from him was received.

Note, however, that in Bulgarian, the adverbial S-adjunct can be preceded by the subject:

(32) Пенка сега му шие риза.

Penka now him-dat.-cl. sew shirt.

Penka is now sewing a shirt for him.

(33) Пенка вчера получи писмо от него.

Penka yesterday received letter from him.

Yesterday Penka received a letter from him.

The data indicate phrasal status for both the [V + internal arguments] and the [subject + V + internal arguments] groups. The structure of S2 acquires the form:

*[Subject position *[Verb + complements]],

with adjunction sites (marked as ‘*’) in front of both the subject phrase position and the verb phrase group.

3.1. 3. Rewriting S as PP S

In the TB, prepositional phrases (PPs) as sentential adjuncts usually occupy a position after CONJ and at the head of S2:

(35) Над широкото поле трепере адска мараня.

Over large-the field shivers infernal haze.

An infernal haze shivers over the large field.

(36) В миг млъкна дружна песен и полето затихна.

In second ceased common song and fields-the became- quiet.

The common song ceased in a second and the field became quiet.

(37) (...) из нивите се не мяркаха работници.

(…) in fields-the lex.-cl. not show-up-past workers.

(…) no workers could be seen in the fields.

In the majority of cases, the presence of a PP-adjunct in initial position blocks the appearance of the subject in the ‘sentence front’. Examples (35)–(37) indicate that the position occupied by the PPs and the position otherwise occupied by the subject phrase (the external argument), is identical, say WP. Both the argument NP and the adjunct PP are probably inserted in the structure in positions within / under VP and, for some reason, move forward. Then the movement of the subject to WP would block the forward movement of PP and vice versa. This hypothesis finds confirmation in the construed examples (38a) – (38b) and (39a) – (39b) where the (a) examples, without being totally ruled out, are highly improbable and would involve emphatic stress on the NP following the initial PP:

(38) Над широкото поле трепере адска мараня.

Over large-the field shivers infernal haze.

An infernal haze shivers over the large field.

(38a)?? Над широкото поле адска мараня трепере.

Over large-the field infernal haze shivers.

(38b) Адска мараня трепере над широкото поле.

Infernal haze shivers over large-the field.

(39) Из полуоткрити уста бе потекла струйка алена кръв.

From half-open mouth had streamed trickle scarlet blood.

From the half-open mouth, a trickle of scarlet blood had streamed.

(39a) ?Из полуоткрити уста струйка алена кръв бе потекла.

From half-open mouth trickle scarlet blood had streamed.

(39b) Струйка алена кръв бе потекла из полуоткрити уста.

Trickle scarlet blood had streamed from half-open mouth.

The possibility for forward movement to WP of both Noun Phrases and Prepositional Phrases, of both verbal arguments and adjuncts indicates that the position is not reserved for constituents with a specific argument/non-argument, external/internal argument or complement/adjunct status. These observations seem to indicate the feasibility of a Thematic Phrase analysis for WP and to support the postulation of this phrase in work by Rudin (who calls it ‘Topic’ and proposes a second thematic position, ‘Focus’ – Cf. Rudin 1986) and others.

3.1.4. Rewriting S as NP S

The TB for Bulgarian contains instances of two major types of NP-adjunction to S: Vocatives and Nominal modifiers.

Vocatives.

The Vocative is the only case marker of the noun which Bulgarian has retained from Indo-European. The nominal inflexion, together with a following pause, marks the fact that the phrase does not form part of the verb’s arguments. The TB only provides examples of their adjunction to initial position – which is also their typical position:

(40) Бате, не мож позна Пенкиния глас.

Elder-brother-voc., not can recognize Penka’s voice

Elder brother, you won’t be able to recognize Penka’s voice.

(41) Боже, дано лъжа бъде!

God-voc., let lie be!

God, let this be a lie!

(42) Мамо, ще те попитам нещо (...)

Mother-voc., will you-cl. ask something.

Mother, I will ask you something.

The sentence front, however, is not the only position for Vocatives. They can also be S-final or S-internal as in the examples below:

(43) Не мож позна Пенкиния глас, бате!

(44) Не мож, бате, позна Пенкиния глас!

(45) Не мож позна, бате, Пенкиния глас!

Note also the example from the Bulgarian poet Hristo Botev, cited in this context by T.-Balan (1940: 457):

(46) Но кажи какво да правя кат си ме майкородила със сърце мъжко, юнашко?

But say what to do when have me-cl., mother, born with heart man’s, hero’s.

But tell me what to do, mother, when you have given me the heart of a courageous man?

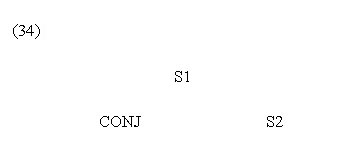

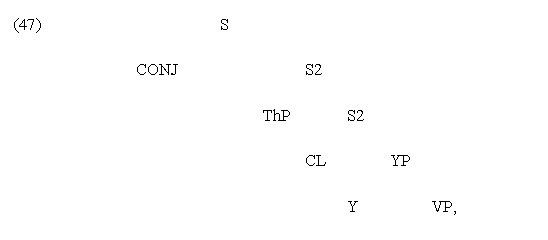

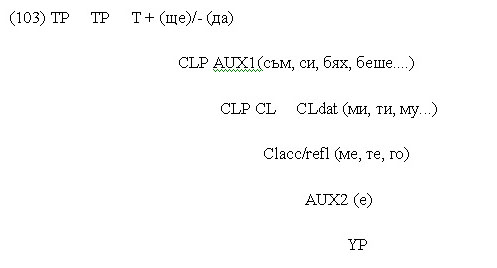

The adjunction possibilities demonstrated above indicate a position of the main verb within a maximal projection above VP (i.e. the V + arguments group). Example (46) indicates the appearance of the clitic group within a constituent which is not identical to VP. The analysis of the data thus allows the following correction of the initial ‘S -> NP VP’ rewrite rule:

where YP is yet to be defined.

Other Nominal Adjuncts

The adjunction positions defined for Vocatives can also host NP modifiers:

(48) Една сутрин в горатасе чуха три весели, пълни с живот подсвирквания.

One morning in forest-the refl.-cl. heard three gay, full of life whistles.

One morning, three gay whistles, full of life, were heard in the forest.

(49) Пенка тоя пътй се видя по-хубава от всякога.

Penka this time her-dat.-cl. refl.-cl. seemed more beautiful than ever.

This time Penka seemed to her more beautiful than ever.

(50) Бог тия днидаде страшна жега.

God these days gave terrific heat.

God gave terrific heat these days.

The possibilities for adjunction in the above examples support the structure outlined in (44) above.

3.1.5. Rewriting S as S’ S

Before proceeding to the analysis of the structure of S-basic (S3), I will devote some place to the rule introducing subordinated clauses (S4). In the present top-down analysis, this rule often precedes S (-basic) rules.

Following earlier syntactic tradition, the TB marks subordinate clauses as S’. The category is re-written with the rule, first introduced by J.W. Bresnan (Bresnan 1970):‘S’ –> COMP S’, where COMP (Complementiser) unites a number of elements in complementary distribution.

Although the position COMP is a typical element of S4 clauses, this node can also appear at the head of any S – mainly, but not only, in exclamations:

(51) Боже, акоме види Стойко!

God-vocative, if me-acc.-cl. sees Stoyko!

God, if Stoyko were to see me!

(52) Далине иде оттам, дето е той – помисли Пенка.

Whether not come from-there, where is he – thought Penka.

Might he not be coming from where he is? – thought Penka.

In the majority of cases, however, the complementiser is a marker of syntactic subordination: S4 constituents are usually headed by a phonetically non-null element in COMP. In our TB, the following are the typical COMP fillers:

- Ако [‘ako’ – if]:

This complementiser introduces conditional clauses. S4-type clauses, introduced by ако usually precede the main clause:

(53) Ако схванеш Пенкиния глас, (...)

If catch-you Penka’s voice

If you catch Penka’s voice (…)

- Да [da – ‘if’]:

If да is synonymous to ако, the subordinate clause as a rule precedes the main clause:

(54) Да би могла, и тя би му пратила поздрав.

If could-she-conditional, and she would him-dat.-cl. send greeting.

If she could, she would also send him her greetings.

(55) Да пее сама, през море да е – ще я позная!

If sing alone, through see be it – will her-acc.-cl. recognize- I.

If she sang alone, I would recognize her even across the sea!

- Да [da – ‘to’, ‘in order to’, ‘so as to’]:

All subordinate clauses in the TB where this complementiser is realized follow the main clause:

(56) Бяла пребрадка небрежно бе паднала на чело, дазасени хубавото й лице.

White kerchief carelessly had fallen on forehead, to shade beautiful-the her-gen.-cl. face.

A white kerchief had carelessly fallen on her forehead, to shade her beautiful face.

Some authors (e.g. Penchev 1998) analyse Bulgarian да in the so-called ‘да-construction’ (the functional equivalent of the infinitive) (as in 55) as a complementiser:

(57) Не иска даим отнеме лелеяната в душа надежда

Zero-subject-not want to them-dat.-cl take-away cherished-the in soul hope.

He does not want to deprive them of the hope, so cherished in their souls.

The insertion of a subject, however, indicates that the position of this type of да is invariably under the ThP-position and is hence S-internal:

(58) Не иска той даим отнеме (…)

Ne iska toy da im otneme

Not want he to them-dat.-cl. take-away (...)

The phrase following да, though finite, is one of tense neutralization and, therefore, cannot be considered to form a canonical ‘tensed clause’. As to the Bulgarian infinitive – which, though rare, is nevertheless attested in the corpus, it cannot be preceded by a subject NP – its subject is always co-referential with that of the modal verb invariably preceding it (Cf. (59) below). Unlike the English bare infinitive, however, it can be separated from the modal by clitics, adjuncts or both – Cf. the construed examples (60a) and (60b):

(59) Бате, не мож познаПенкиния глас!

Elder-brother-Voc., not can recognize Penka’s voice!

Elder brother, (I bet) you can’t recognize Penka’s voice!

(60) Ако ти не мож й позна гласа, та аз ли ща бре, синко?

If you not can her-gen.-cl. recognize voice-the, then I interr.-cl. will, now, son-Voc.

If you can’t recognize her voice, how will I do it, son?

(60a) Не мож сега познагласа на Пенка.

Not can now recognize (infinitive) voice-the of Penka.

You cannot recognize Penka’s voice now.

(60b)Не мож сега й познагласа.

Not can now her-gen.-cl. recognize voice.

You cannot recognize her voice now.

- Като че[‘kato che’ – as if] appears in the TB in S4-type constituents following the main clause:

(61) (...) клоните му потънаха в (...) цветове, като чеслънчеви лъчи бяха паднали само върху него.

Branches-the its-gen.-cl. got-covered with blossoms, as if sun’s rays had fallen only on it.

Its branches got covered with blossom, as if sun rays had fallen on it alone.

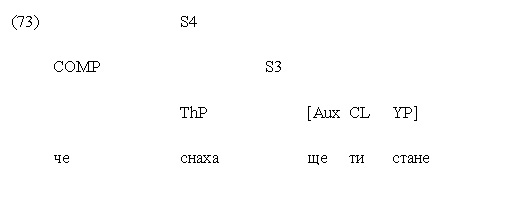

- Че [‘che’ – that] is the typical complementiser. Although a subordinate introduced by че can potentially precede the main clause, this possibility is not exemplified in the TB:

(62) (...) да знаеш, че наистина снаха ще ти стане

to know that really daughter-in-law will to-you-dat.-cl. become-she.

know that she will really become your daughter-in-law.

(63) и ето, че някъде далече се поде самичък глас (...)

and here, that somewhere far refl.-cl. strike-up lonely voice.

And here goes, from somewhere afar, a lonely voice struck up.

Unlike typical complementisers, relatives appear in relation to another position in the structure. In the simplest case, there is abstract co-indexing of two correlative positions, as e.g. in the case of дето [deto – where (rel.)] – Cf. (64), who (rel.) – Cf. (65), which (rel.) – Cf. (66), where (65) and (66) are construed examples:

(64) Дали не иде оттам, дето е той – помисли Пенка.

Whether not come from-there, where is he – thought Penka.

Might it not be coming from where he is – thought Penka.

(65) Това е жената, дето ни продаде бонбоните.

This is woman-the who to-us-dat.-cl. sold sweets-the.

That is the woman who sold us the tickets.

(66) Това е палтото, дето Коста ми го купи.

This is coat-the, which Kosta to-me-dat.-cl. it-acc.-cl. bought.

This is the coat, which Kosta bought me.

A specific feature in the above cases is that the ‘introducing’ element is morphologically unmarked and can be correlated with both categorially different positions and with elements of different morphological shape within the same category.

In most cases, however, the status of the introducing element is well-defined: on the one hand, it is clearly associated with a particular position, a particular category or form; on the other, it does not seem to be introduced in the structure with a simple singulary transformation – in the manner of the movement of PP- and NP-over-S – Cf. e.g. the ungrammaticality of the construed word order variant of (28) above, listed here again as (67):

(67) Докъде ти око види, се люлеят златни ниви (...)

Upto-where your-gen.-cl. eye sees, refl.-cl. swing golden fields.

As far as the eye can see, golden fields are swaying.

(68) *Око ти види докъде, се люлеят златни ниви.

Eye your-gen.-cl. sees upto-where, refl.-cl. swing golden fields.

The TB indicates a higher position (probably COMP) for relatives and a lower (ThP or Focus – as in Rudin op. cit.) position for WH-words – as indicated by the examples (69)-(70) and (71), respectively:

(69) Кого е видял Петър?

Who-acc. has seen Petar?

Who has Petar seen?

(69a) ?? Кого Петър е видял?

Who-acc. Petar has seen?

(70) Какво пак е направила Тити?

What again has done Titi?

What has Titi done again?

(70a) ??Какво пак Тити е направила?

What again Titi has done?

(71) Това е човекът, когото Иван е видял.

That is man-the who-acc-the John has seen.

That is the man, whom John has seen.

3.2. From WP to V: the structure of S3.

3.2.1. Adverbial Adjunction and Bulgarian Phrase Structure

As demonstrated in the analysis in 3.1. above, the TB indicates that the traditional ‘NP-under-S’ position is probably the result of a singulary transformation – syntactic movement to a position of a non-functional nature. This position, following directly COMP, marks the leftmost boundary of the ‘S3-unity’.

The well-established view that adverbial adjunction is a standard test for structure is axiomatically adopted in this study – with the postulations that it cannot be applied to heads or intermediate strings and that it marks the boundaries of phrasal groups (constituents) in syntactic structure. Following the analysis in 3.1. which confirms the view of the subject as VP-internally inserted, the TB data mark out the following adjunction sites:

1/ Under the complementiser COMP and above ThP, as a ThP-adjunct:

(72) Да знаеш, [че наистина[снаха ще ти стане]S3]S4].

To know that indeed daughter-in-law will to-you-dat-cl. become.

Know that she will really become your daughter-in-law.

2/ Between ThP and VP:

a. Over V, marking the bounds of VP or YP:

(74) [Грив гълъб усамотено[префюфюква с крила към гората.]YP]S3]

Grey dove lonesomely flaps with wings towards forest-the.

A grey dove lonesomely flaps with wings over the forest.

b. Over the ad-verbal ‘Auxiliary+clitic’ group:

– Over the auxiliary verb, marking the bounds of an intermediate phrase between S3 and YP, including the clitic group. This phrase is labelled here XP:

(75) [Тя скришом[беше му пратила вече едни чорапи]XP]S3].

She secretely be-Aux to-him-dat.-cl. sent already some socks.

Secretely, she had already sent him some socks.

– Over a pronominal / reflexive clitic:

(76) Тя се обръща и [весело[го задява.]XP]S3.

[She refl.-cl. turns and gaily him-acc-cl. teases.]

She turns round and teases him gaily.

3/ Between the auxiliary verb and the main verb, separating XP from YP:

(77) Град да бе паднал, не [би тъй[убил сърцата]YP]XP.

Hail to be-past fall-ed2, not would thus kill-ed2 hearts-the.

Had even hail fallen, it wouldn’t have thus killed the hearts.

4/ Between the main verb and its complements:

a. Between the main verb and the Direct Object NP:

(78) Тя скришом беше му [пратила вече[едни чорапи[VP? / NP?]YP].

She secretly be-past to-him-dat.-cl. sent already ones socks.

She had secretly already sent him some socks.

b. Between the NP and PP complement:

(79) и заехтя [полето пак[от смях и песни]PP]VP]

and began-to-echo field-the again from laughter and songs.

dnd the field began to echo again with laughter and songs.

5/ Under VP:

(80) [Неуморно [те жънат]S3 там]S3.

Tirelessly they reap there.

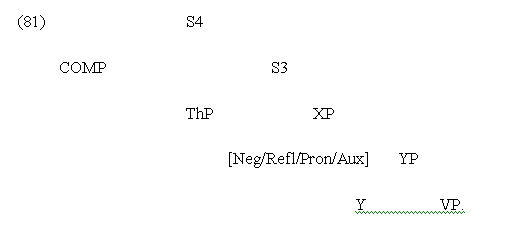

The TB adverbial adjunction examples outline the following structure:

3.2.2. The clitic group.

The structure of the clitic group between XP and YP can easily be derived from the TB. Querying for Aux, Neg, Refl, Clarg and ДАresults in the following strings:

Neg under VP:

(82) Узрялото жито нечака.

Ripe-the corn not wait.

Ripe corn does not wait.

(83) Град да бе паднал, неби тъй убил сърцата.

Hail of be-aux. fall-ed2, not be-aux thus kill-ed2 hearts-the.

Had hail fallen, it would not have thus killed the hearts.

The examples indicate a position for Neg over Aux and V:

(84) Neg [Aux V] XP.

This position, though not the only one for Neg, is its dominant site in the database.

Refl under VP:

(85) Тя сеобръща и весело го задява.

She refl-cl. turns and gaily him-acc.-cl. teases.

She turns and teases him gaily.

(86) Слънцето сее спряло огнено и немилостиво в небесата.

Sun-the refl.-cl. be-3rd sg. pres. stop-ed2 fiery and merciless in skies-the.

The sun has stopped fiery and merciless in the skies.

The examples indicate that the position of the reflexive clitic is to the right of both да and the dative clitic. In some (non-literary) examples, such as (86) below, Negation (Neg) appears under the reflexive clitic, as a YP-adjunct. In modern literary Bulgarian, however, its position would preferably be above the reflexive clitic, as an adjunct to XP – Cf. (86a):

(87) [[Из нивите]WP [се [не[мяркаха работници]YP]YP]XP]S3].

(87a) [[Из нивите]WP [не[се мяркаха работници]XP]XP]S3].

Pronominal clitics:

(88) Зарадва гитой с благодатни майски дъждове.

Delighted them-acc.-cl. he with blessed May rains.

He delighted them with blessed rains in May.

(89) Майко, я си почини и гипослушай!

Mother-Vocative, do refl.-cl. rest and them-acc.-cl. listen- to!

Do have a rest, mother, and listen to them!

(90) Кой ли ще муя изоре?

Who interr.-particle will to-him-dat.-cl. plough?

Who will plough it for him?

(91) Нали няма да мисе караш, мамо!

Will-you, you-won’t to me-dat.-cl. refl.-cl. scold, mother!

You won’t scold me, will you, mother!

The TB indicates that the dative clitic is positioned to the right of да, ще, Neg or Aux. Immediately to the right of it is the position of the Accusative or Reflexive clitic. These latter two never appear together, which is an indication of complementariness: they occupy the same position. Immediately to the right of the Reflexive / Accusative clitic position, before V, is the position for the 3rd p. sg. form of the auxiliary.

The TB contains quite a few examples where the dative clitic position is filled with a genitive clitic, clearly landing there from a position lower in the structure:

(92) (...) и не имсе чуе гласът.

( ) and not to-them-gen. cl. refl.-cl. hear voice-the.

(…) and their voice is not heard.

(93) Ако ти не мож йпозна гласа, та аз ли ща бре, синко?

If you not can her-gen.-cl. recognize voice-the, then I interr.-cl. will, now, son-Voc.

If you can’t recognize her voice, how will I do it, son?

This phenomenon, known as ‘clitic climbing’, has a very specific manifestation in Bulgarian.

The Auxiliary Positions.

Even though the TB contains mainly the 3rd sg. form of the auxiliary, this is obviously not the only available form. Substitution of ‘e’ with forms for other persons and for the plural indicates that there are two distinct auxiliary (Aux) positions between XP and YP. Both positions are under да / ще and Neg, in a phrase which can be separated from the rest of the Verb phrase – Cf. (94)–(95) below and their transformations:

(94) Възможно е Пенка да (не) му го едала.

Possible is Penka to (not) to-him-dat.-cl. it-acc.-cl. be-3rd sg. pres. given.

It is possible that Penka has not given it to him.

(94a) [Възможно е] вчера[Пенкада(не) му го е дала].

(94b) [Възможно е] [Пенка] вчерада(не) му го е дала.

(94c) Възможно Пенка[да(не) му го е] вчера дала.

(94c) Vazmojno e Penka [da (ne) mu go e] vchera [dala].

(94d) *Възможно еПенкада(не) му го вчера е дала.

(94e)*Възможно еПенкада(не) вчера му го е дала.

(94f) *Възможно е Пенкада(не) му вчера го е дала.

(95) Възможно е да не са му го дали.

Possible is to not be-3rd pl. pres. to-him-dat.-cl. it-acc. cl. given.

It is possible that they have not given it to him.

(95a) ?Възможно е да не са вчера му го дали.

(95b) ?Възможно е да не са изобщо му го вчера дали

Possible is to not be-3rd p. at all to-him-cl. it-acc. cl. yesterday given.

(95b) also indicates the possibility for pronominal clitics to appear in a phrase, separate from the first auxiliary position:

(96) [да не са ] изобщо[му го] вчера[дали].

The status of да and ще is a controversial one in Bulgarian linguistics. They cannot appear in the first Aux-position, because they are both particles, not verbs (even though ще has developed, historically, from the verb of volition). Both да and ще are directly related to Tense, which could be an indication of the nature of the projection(s?) they head: ще marks Futurity, while да in T marks a neutralization of the temporal oppositions in the clause, i.e. (–T). If this hypothesis is correct, the ad-verbal clitic complex would acquire the form:

(97) [TP Neg[TP[лиTP[T +(Aux1 Cldat Clacc/refl Aux2) YP]]]]]

Example (98) indicates an adjunction position of the ThP type in front of the lower verbal projection, temporarily labeled here YP:

(98) Като те е господ научил, послушай го, детето ми!

Since you-acc.-cl. be-3rd sg. pres God taught, listen to-him- acc.-cl., child my-gen.-cl.

Since God instructed you, listen to him, my child!

3.2.3. The Verb Phrase.

VP-internal structure is presented in the ‘first cycle’ grammar in its traditional form – with an external argument, realised as a specifier, and one or more complement positions. The distinction between subject and complement has serious structural and semantic motivation and is well established in linguistics. The TB does not give grounds to revise this distinction. On the other hand, it does provide examples of deviations from the canonical Subject – Direct Object (D.O.) – Indirect Object (I.O.) pattern – Cf. (99), with a PP-Indirect Object preceding the subject and (100), (101), where the PP-I.O. precedes the NP-Direct Object:

(99) Запалиха се от страст плодородните й недра.

Catch-fire-past with passion fertile-the her-possessive clitic bosom

Her fertile bosom caught fire with passion.

(100) Тя обходи с поглед цялата Стойкова нива.

She swept with look whole-the Stoyko’s field.

She swept Stoyko’s whole field with her eyes.

(101) Слънцето посипваше с лъчи младата работница.

Sun-the covered with rays young-the worker.

The sun covered with its rays the young worker.

4. Discussion.

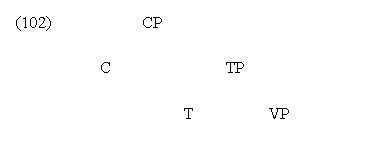

Already in the Theory of Government and Binding (Chomsky 1981), functional categories were postulated as an important element of syntactic structure – initially as categories of a morphological type, selected by a category standing higher in the structure. Later, these categories were reanalyzed as functional superstructure projected from the Lexicon., including AGRSP, AGROP and TP. Following Chomsky 1995, the ‘agreement’ phrases were discarded. The following general structure was proposed:

The TB data do not support the introduction of separate agreement phrases. There is ample support for at least one syntactic position above C, but the data demonstrate that this position is related neither to syntactic function, nor to morphological categories. It has thematic character.

Thus several layers of structure, as manifested in the TB, top the Verb Phrase. Immediately under the non-functional position ThP is a phrase, to which Polarity elements (negative and interrogative particles) can adjoin and in the head of which appear the Tense markers да and ще. Under this phrase is another phrase of a verbal type, with syntactic positions for auxiliaries and pronominal clitics. The string ‘dative clitic+accusative/reflexive clitic+3rd sg. pres. auxiliary’ forms a compact group, probably attached to the head of the first Auxiliary position. Under this phrase is yet another phrase of verbal character, to which the negative and interrogative particles can also adjoin. This phrase may contain additional auxiliary verb positions. The possibility for the Bulgarian verb to be separated from its arguments by adverbial and other adjunctive material indicates that its syntactic position is above its insertion position in VP.

The data support the identification of XP as TP. In the structure of Bulgarian, TP appears with a complex structure of the type:

A possible candidate for YP is AspP – an Aspect phrase under TP, proposed by a number of linguists – Cf. Tenny 1987, Borer 1993, Schoorlemmer 1995, Verkuyl 1995. The argumentation of both TP and AspP follows Grimshaw’s definition of functional superstructure (Grimshaw 1991): if Aspect or Tense are grammatical categories of the verb, the existence of the functional projection follows from general principles of structure. The possible insertion of adjuncts between the V-head of VP and the subject or complements strongly supports an automatic positioning of the Bulgarian Verb in the head of AspP. As to the surface realization of the subject and complements, in Bulgarian this seems to be driven by their communicative value.

5. Concluding Remarks

On a general plane, the paper illustrates the possibility to integrate ideas and methods from two previously opposed approaches to language study in CL applications. More specifically, an attempt was made to implement the idea of cyclic construction of formal grammars. The analysis of the data allowed the reanalysis and reformulation of a number of principles and categories of simple phrase structure grammar:

Additional arguments in favour of the adoption of the principle of binary branching in the analysis of coordination structures were provided by conditions on the appearance of clitics. On the other hand, the structure of the clitic complex under TP does not seem to lend itself naturally to such analysis.

A differentiation between S-sentence (S1, S2) and S-clause (S3, S4) was shown to be helpful for the formulation of more precise rules of structure-building. This differentiation entails a revision of the recursion rules for S.

The rewrite rule ‘S -> NP VP’ proved to be inadequate. At a first step, the NP position was reanalysed as ThP – a structural site for thematic elements – , which in turn favoured a ‘subject-under-VP’ analysis.

A sentence front and VP-front was exemplified, including Conjunction (CONJ), Complementarization (COMP), ThP (non-functional), TP (+Clitics) and AspP positions.

Notes

1 Project conducted by M. Stambolieva in the period 1992-1994 and funded by the National Science Foundation of Bulgaria.

2. The syntactically annotated short stories by Elin Pelin, are Войнишка нива and По жътва.

Bibliography

Aarts 1991. Jan Aarts. ‘Intuition-Based and Observation-Based Grammars’. English Corpus Linguistics (Studies in Honour of Jan Svartvik). Karin Aijmer and Bengt Altenberg. Longman, London and New York. Pp. 44-63.

Borer 1993. H. Borer. Parallel Morphology. Ms., Utrecht University/Univesity of Massachusetts at Amherst.

Bresnan 1970. J. W. Bresnan. ‘On Complementisers: Towards a Syntactic Theory of Complement Types’. Foundations of Language 6, pp. 297-321.

Chomsky 1970. N. Chomsky. ‘Remarks on Nominalisation’. In: R.A. Jacobs and P.S. Rosenbaum, English Transformational Grammar, pp. 185-221.

Chomsky 1981. Noam Chomsky. Lectures on Government and Binding. Foris, Dordrecht.

Chomsky 1995. N. Chomsky. ‘A Minimalist Program for Linguistic Theory’. In: The View from Building 20. K. Halle and S. Keyser (eds.), MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachesetts, pp. 1-52.

Grimshaw 1991. J. Grimshaw. Extended projections. Ms, Brandeis University.

J.-Balan 1940. А. Теодоров-Балан. Нова българска граматика. София.

Jackendoff 1977. R. S. Jackendoff. X-bar syntax: A Study of Phrase Structure. MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Leech 1987. Geoffrey Leech. ‘General Introduction’. In: The Computational Analysis of English (A Corpus-Based Approach). R. Garside, G. Leech, G. Sampson (eds.) Longman, Essex, pp. 1-17.

Penchev 1993. Йордан Пенчев. Български синтаксис. Управление и свързване. Пловдив, издателство на Пловдивския университет.

Penchev 1998. Йордан Пенчев. Синтаксис на съвременния български книжовен език. Пловдив, 1998.

Rudin 1986. Catherine Rudin. Aspects of Bulgarian Syntax: Complementizers and WH-Constructions. Slavica Publishers, Columbus, Ohio.

Schoorlemmer 1995. Maria Luisa Schoorlemmer. Participial Passive and Aspect in Russian. OTS Dissertation Series, Utrecht.

Tenny 1987. C. Tenny. Grammaticalizing Aspect and Affectedness. MIT Dissertation.

Verkuyl 1995. Henk J. Verkuyl. Events as Dividuals: Aspectual Composition and Event Semantics. Ms. OTS, Univeristy of Utrecht.

Wackernagel 1892. “Ube rein Gesetz der indogermanischen Wortstellung”. In: Indogermanische Forschungen 1, pp. 333-436.