7.15 2008 Chemistry Nobel Prize goes to those who lit up cells

http://arstechnica.com/news.ars/post/20081008-2008-chemistry-nobel-prize-goes-those-who-lit-up-cells.html

By John Timmer | Published:

October 08, 2008 - 04:47PM CT

Many of the techniques that

biologists use for looking at cells and organisms involve taking the equivalent

of a static snapshot of the state of these systems. But life isn't a photo;

it's a movie, dynamic and changing. This year's chemistry

Nobel Prize goes to a trio of researchers that found and developed an

obscure protein from a jellyfish and developed it into a system that has given

us an unprecedented view of the movie of life.

The protein has a name, Green

Fluorescent Protein (GFP), that tells you everything significant about it. Lots

of organisms have some sort of bioluminescent capacity, but most of these tend

to involve several proteins and/or additional chemicals. The firefly protein,

luciferase, is an example of this: it glows, but only if provided with a very

specific chemical, which gets used up in the process.

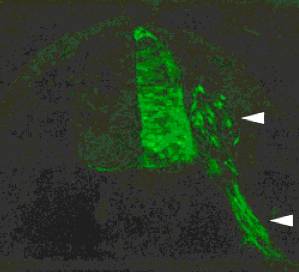

GFP is different. Once a cell produces it, some of the amino acids that make up the core of the protein undergo a series of spontaneous reactions that require only oxygen. This ultimately produces a structure in the protein that can absorb ultraviolet light and emit a bright shade of green in response. Because only oxygen is required for this reaction, any cell that can produce GFP, from bacteria to humans, can potentially glow green. Because no extra processing is needed, even living cells can be imaged using GFP.

GFP expressed in nerve cells lights up the

axons they extend from the developing

spinal cord. Credit: me.

The prize recognizes three

key steps in the development of GFP as a biological tool. One of the three

Laureates, Osamu Shimomura of Woods Hole's Marine Biological Lab, is cited for

his isolation and basic characterization of the protein. Shimomura's careful characterization

of the chemistry of the protein ultimately allowed other researchers to clone

the gene that encoded the protein. Both Shimomura and the cloners, however,

never looked into the origin of its fluorescent properties; a paper describing

the gene contains the quote, "It is very unlikely that the chromophore

forms spontaneously."

The second Laureate, Columbia

University's Marty Chalfie, gets credit for that. When not distracted by

teaching this author undergrad genetics, Chalfie obtained a copy of the DNA

encoding the gene and found that it happily glowed green when expressed in

bacteria, even though these cells lacked the jellyfish enzymes and chemicals

that were still thought to be needed. Correctly recognizing that the protein

could glow on its own, Chalfie expressed it in his experimental organism of

choice, the transparent roundworm C.

elegans. The worms also glowed, and soon Chalfie was imaging

individual cells as the organisms developed.

The original GFP wasn't

perfect, however, as it had a tendency to lose its ability to glow, and, for

technical reasons, green isn't the most convenient color. Roger Tsien of UCSD

received a Nobel for the various improvements he made to GFP. By making various

mutations in the gene, he improved its stability and altered the wavelength of

the light it emits, creating Cyan-FP and Yellow-FP variants, among others.

Tsien has also looked further afield, developing Red-FPs based on a protein

isolated from corals.

In the mean time, the various

FPs have changed the way we look at cells. Hook them up to DNA sequences that

cause the gene to be expressed in specific cells, and those cells glow,

allowing their development to be tracked in real time in everything from worms

to mice. Fuse GFP to a protein that binds to DNA, and the chromosomes can be

tracked as cells duplicate their DNA and divide. Individual cells, proteins,

parts of cells—basically, any place you can attach or ship GFP to—can be imaged

in living

cells and organisms.

For their part in making life

into a movie, these scientists are taking home a well-deserved Nobel Prize.

Further reading:

The Nobel Prize's scientific

background (PDF