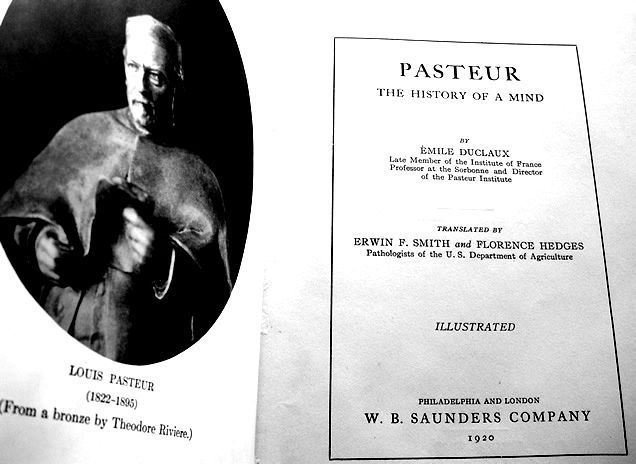

7.34 History of a Mind

Pasteur

|

Pasteur - The History of a Mind,

a perspective "Pasteur: The History of a Mind" was

written by Emile Duclaux (1840-1904) and published in France one year after

Pasteur's death in 1895. Emile Duclaux followed the teachings of

Pasteur, entered his laboratory as his assistant, was later his collaborator

and actively participated in the founding of the Pasteur Institute. As

his readers we are indebted to him for achieving the difficult task of giving

posterity the most accurate genesis of Pasteur's discoveries.

Pasteur's rare gift was his vision of the world,

which he transformed by demolishing dogmas, stamping out erroneous views and

fiercely imposing his own insightful ideas. At least the reader of

"Pasteur - The History of a Mind" can grasp Pasteur's intuitive

imagination and extraordinary skill for experimentation. The reader can

further apprehend the genius in Pasteur by evaluating the colossal

advancement in biological knowledge resulting from his studies on crystals,

lactic and alcoholic fermentation, spontaneous generations, wines and

vinegars, diseases of silkworms, manufacture of beer, etiology of microbial

diseases, and vaccines. In the early years of his life as chemist, while

doing research on the left-right molecular asymmetry and its mode of action

on polarized light, Pasteur was introduced to the realm of life. A

living fermentative organism became a "laboratory of dissymmetrical

forces" and, as Pasteur soon discovered, could differentiate between the

left- and right-handed activities of a molecule, and utilize one form without

touching the other. Naturally the young savant approached the question

of fermentations and later spontaneous generations. At the time Pasteur initiated his studies on

fermentations there was quite a confusion of ideas and a multitude of

arguments, particularly it was largely accepted that yeast was not involved

in fermentation. Carried by the knowledge gained during the course of

his studies on asymmetry, Pasteur immediately considered fermentation as

"a vital act". A series of brilliant experiments followed

leading Pasteur to discover the reproduction of "ferments", the

effect of acidity on fermentation, the use of antiseptics to separate

ferments, the products of fermentation and finally the division between

aerobic and anaerobic life. Now Pasteur could no longer believe in

spontaneous generations as it denied the notion of specificity he had just

introduced with his studies on fermentation. Before Pasteur, the debate on spontaneous

generations was mislead by experiments lacking reproducibility. Pasteur

who had ingeniously defined a clear medium to study his ferments was ready to

enter the arena. Experiments confirmed his previous belief and the

partisans of spontaneous generations were given correct reasons for their

experimental failure. Thereafter heated debates occurred in front of

committees named by the Academy of Science and, despite the fact that some

experimental results were given improper explanations, the recognition of the

"germ theory" prevailed. From this resulted safe conditions

in conducting experiments by the introduction of autoclaves as well as

techniques such as sterilization by flaming. Pasteur's discovery of the bacterial action in

the production of wines and vinegars had also practical consequences.

Industrial methods in the production of wines and vinegar were greatly

improved and the concept of pasteurization, the protection against microbes

by the action of heat, then introduced. What remains distinctive is

Pasteur's classical demonstration of the action of oxygen on wine. In 1865, Pasteur's destiny shifted towards a new

course when he accepted to study the disease of silkworms to which he devoted

six years. He discovered that diseases may result from the development

of a microbe in healthy tissues of its host. Pasteur's orientation

towards pathology would ultimately lead him to make a connection between

contagion and heredity. By studying the contagious diseases of the

silkworms he addressed for the first time the question of "receptivity

to germs". He was on the path leading towards immortal fame. The consecutive study -the manufacture of beers-

was started by Pasteur with the motivation of raising the quality of French

beers to German standards. Ultimately Pasteur's book on brewing will

reflect the fact that his mind was at that time preoccupied by questions more

crucial to him than the problems of the French brewers. The specificity

of his germ theory had been attacked by the partisans of the transformation

of microscopic species. The notion of spontaneous generation of yeast

was resurfacing. It is one more time by experimentation that Pasteur

demonstrated that a microscopic species does not transform into another

thereby establishing the specificity of microbial diseases. Furthermore

he described the adaptation of microscopic species to aerobic or anaerobic conditions

giving birth to the physiological theory of fermentation. Pasteur had now studied his microbes for twenty

years. The general current of ideas about diseases did not support the

germ theory, and diseases were generally considered the results of

"forces of the physico-chemical order". Anthrax, despite

Davaine's pioneer work and Koch's brilliant demonstration of the role of the

spore in the etiology of this disease, was still not regarded as a bacterial

disease. In his final studies, Pasteur developed vaccines

for chicken cholera, anthrax and rabies. As he gained public confidence

his popularity increased thereby allowing the creation of the Pasteur

Institute. By studying the transmission of bacterial diseases he gave a meaning to the notions of attenuation and virulence. He apprehended the

concept of natural immunity and finally foresaw the cellular theory of

immunity later demonstrated by Metchnikoff and his discovery of the white

corpuscles of the blood. Pasteur was a savant, a man of the

laboratory. His life echoed Alfred Lord Tennyson's poem

"Ulysses" [1842] in his final verse: "To strive, to seek, to find, and not to

yield." |

|

Suggested Reading: Scientific papers by Louis

Pasteur, in The Harvard Classics, Volume 38, Part 7 On the antiseptic principle of the

practice of surgery by Joseph Lister, in The Harvard Classics, Volume

38, Part 6 The

Pasteur Institute by François Jacob, 1998, at Nobelprize.org |